|

Anna M. Cienciala (hanka@ku.edu) |

History

557 Lecture Notes |

Spring

2002 (Revised Fall. 2003, spring 2008, Aug-Sept... 2009, April, June2010,

Feb. 2012, Sept. 2013)

|

|

|

LECTURE 16.

THE COMING OF THE WAR AND EASTERN EUROPE IN WORLD WAR II.

A. The British Guarantees to Poland,

Romania and Greece, the Nazi-Soviet pact, and the Outbreak of World War II

[This text is based largely on the

authorís articles, cited here. See also new publications cited in this

lecture.]

I would like to thank Prof. Jean

Sedlar of the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown, PA, for her very helpful

comments and corrections, esp. on the Balkans. Her surveys of East Central

Europe (including Finland] and South Eastern Europe in World War II, published

in 2008 --see Bibliography-- are cited where pertinent.]

I .British Attitudes toward

Germany in the Aftermath of Munich.

In early October 1938, the U.S.

Ambassador to Britain, Joseph Patrick Kennedy (1888-1969, father of JFK,

Robert and Ted Kennedy, Ambassador 1937-40), reported what Br. For. Secretary

Lord Halifax had told him about British and French policy toward Germany.

Halifax said they intended to strengthen their air defenses and

...after that, to let Hitler go

ahead and do what he likes in Central and South-Eastern Europe. In other words,

there is no question in Halifaxís mind that reasonably soon Hitler will make a

start for Danzig, with Polish concurrence, and even if he decides to go into

Roumania it is Halifaxís idea that England should mind her own business.*

*[Kennedy to the Secretary of State,

October 12, 1938, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United

States, 1938 . vol. I, Washington, D.C., 1955, pp.85-86. This series is

generally referred to as: FRUS].

Halifax put this less crudely in his

letter of November 1, 1938, to Sir Eric Phipps, British Ambassador in Paris,

when he wrote:

Henceforward we must count with German predominance in

Central Europe. Incidentally, I have always felt myself that, once Germany

recovered her normal strength, this predominance was inevitable for obvious

geographical and economic reasons.

*

*[Documents on British Foreign Policy, 3rd

series, vol. III, 1938-1939, London, 1950, doc. no. 285, p. 252].

Thus James Headlam-Morleyís 1925 warning that

German expansion in Central Europe would threaten W. Europe (Lec. Notes 15)

went unheeded. Although some senior officials in the Foreign Office opposed

concessions to Hitler in Central Europe, their views were ignored. The foremost

opponent of appeasement, Robert Vansittart (1881-1957), lost his

position as Permanent Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and thus

head of the Foreign Office, in 1937 to Alexander Cadogan (1884-1968),

who held that post until the end of World War II.

Despite internal opposition and

criticism from some Foreign Office members, and vocal opposition from some

politicians, British statesmen still believed that German expansion in Central

and S.E. Europe would not have any dangerous consequences for Western

Europe. However, British public opinion was deeply divided over Munich.

While there was much admiration for Chamberlain for havinga avoided war, there

was a strong feeling that while the Munich decisions may have been unavoidable,

the Western Powers should make no more concessions to Hitler. Opposition to

Chamberlainís appeasement policy also grew within the Conservative Party; it

was led by Winston Churchill (1874-1965). He had warned against Germany

and given information (sometimes exaggerated) on its rearmament since 1935.

Although he had supported intervention against the Bolsheviks in 1918-19, he

now advocated a "Grand Alliance" of Britain, France and USSR to stop

Hitler.

2. French Attitudes.

French Premier Edouard Daladier

(1884-1970) was very surprised at the welcome he received on landing in Paris

when he returned by air from Munich. He had expected anger at betraying

Czechoslovakia - but was met with cheers and flowers. He said the people did

not realize what had happened. Indeed, after the initial joy at avoiding war had

passed, public opinion polls showed that most French people thought like the

British - - that Munich was unavoidable, but no more concessions should

be made to Hitler.

Unlike Daladier, French

Foreign Minister Georges Bonnet (1887-1973) was a convinced appeaser. On

December 6, 1938, he signed an agreement in Paris with German Foreign Minister Joachim

von Ribbentrop (1893-1946) that the two governments would consult each

other on questions of mutual interest. This was, in fact, like the

Chamberlain-Hitler agreement signed at Munich on September 30 - but

Ribbentrop saw the agreement signed with Bonnet as French resignation

from interest in Central Europe. Bonnet denied this officially in a diplomatic

note of July 1, 1939. However, in a work published after the war he

seemed to confirm Ribbentropís impression. Thus, in his book on the French

Foreign Ministry under the first three republics (published in Paris,1961),

Bonnet wrote that a Franco-German "entente" could have been the first

step to a United States of Europe (!). He also wrote that, at the time,

one could hope Hitler would be clever enough to settle the Danzig-Corridor

question at another conference.* It is clear that this reflected Bonnetís

own hopes in 1938-39.

*[Georges

Bonnet, Le Quai díOrsay sous Trois Republiques, Paris, 1961, p.240,

243-44].

II. Polish-German Relations,

October 1938 - January 1939.

1. On October 24, 1938, Ribbentrop

told Polish Ambasssador Jozef Lipski (1894-1958, Minister, then

Ambassador in Berlin, 1932-39, later in the West), that Germany could offer

Poland a "general settlement" of all outstanding questions.

Ribbentrop proposed that: (1) Poland agree to the abrogation of Danzigís status

as a Free City and its return to the Reich, while preserving all its rights

there, also to a German extra-territorial highway and railway through the

Polish Corridor to Danzig and East Prussia; (2) Poland would join the

"Anti-Comintern Pact."* In return, Germany would guarantee the

Polish-German frontier and extend the Declaration of Nonaggression of 1934 for

25 years.

*[Oct.25, 1936, German-Italian Pact;

Nov. 26. 1936, German-Japanese Pact; Nov. 6, 1937, Italian-Japanese Pact

against the Comintern. These pacts came to be known as the Anti-Comintern

Pact].

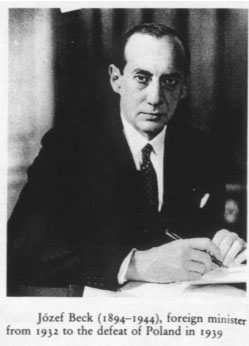

Polish Foreign Minister Jozef

Beck (1894-1944, For. Min. 1932-39) instructed Lipski to give a

negative answer on Danzig , but say that negotiations were possible to

improve German railway traffic and on building a German highway through

the Polish Corridor. This seems to be have been a gambit to gain time, and

there is no trace of any agreement by the Polish "Castle Council"

(President, For. Min., Army Chief,and selected others meeting in the

President's rooms in the Royal Castle, Warsaw) to this project. Finally, Beck said

nothing to the invitation to join the Anti-Comintern Pact, which was equivalent

to a refusal.

Ribbentropís proposal seems quite reasonable. However, we know what

Hitlerís real intentions were from information given by the Danzig

"Gauleiter" (Party district leader) Albert Forster (1902-1950)

to the League of Nations High Commissioner in Danzig, Carl Jakob Burckhardt

(1891-1974, in Danzig 1937-39). In November 1938, Forster told him what he had

just heard from Hitler: The Fuhrer said he would guarantee Polish

frontiers for his own lifetime - but only if the Poles were "reasonable

like the Czechs." Burckhardt heard the same phrase from

German State Secretary Ernst von Weizsacker when he visited Berlin in

December 1938. Thus, it is clear that Hitlerís aim was to make Poland

subservient to Germany. *

*[for details and references to doc.

sources, see info. below on Ribbentrop visit to Warsaw, Jan. 26, 1939.]

Beck played for time

and worked for closer relations with Britain. In this he succeeded, for on December

15, 1938, the British government stated that it would not approve any changes

in the status of Danzig without first consulting with the Polish government.

This meant a defeat for Georges Bonnet, who was pushing for the removal

of the High Commissioner from Danzig as well as the abolition of all League of

Nations involvement in the Free City. This French proposal to Britain came on

the heels of the introduction of antisemitic legislation in Danzig by Forster

in November 1938, just after attacks on Jews all over Germany known as the

"Crystal Night" because of the broken glass.

Halifax rejected Bonnet's proposal because he believed that Britain

might need Col. Beck in the future. It is not clear what Halifax meant by this

phrase, but it seems that he saw Beck as a Polish statesman who

would be willing to give Hitler what he wanted by negotiation, thus avoiding

war. In any case, Halifax certainly believed that the issue could be settled

peacefully.

In December 1938, with the next

League of Nations session in the offing, Beck requested a meeting with Hitler

to find out whether his views on Danzig and the Corridor were the same as

Ribbentropís. The meeting took place in Berchtesgaden on January 5, 1939.

Hitler repeated the Ribbentrop proposals of Oct. 24, 1938, to which Beck

answered that he saw no equivalent for a Polish agreement that Danzig return to

Germany. Ribbentrop pressed Beck on the same issue next day, and received the

same answer.

On returning to Warsaw, Beck

thought briefly of taking up a phrase Hitler used, when he suggested a new

organism, a "Korperschaft" (corporation) to safeguard Polish and

German interests in Danzig. Beck thought that some sort of

"condominium" or joint Polish-German administration might provide a

solution. However, the Castle Council decided that no such Polish proposal

should be made because it would be the first step on the slippery slope to the

loss of Polish independence. B

eck agreed.

There is no clue as to what Hitler

might have meant by "corporation," but the whole thrust of Nazi

propaganda in the Free City -- which the Nazis ruled since winning the

elections in the FCD territory in May 1935 -- was "Heim ins Reich!"

(Home to Germany). Therefore, it is possible to assume that whatever Hitler may

have meant by corporation," it would have meant German sovereignty.

Neither the Polish government nor public opinion could agree to this or to an

extraterritorial German Corridor through the Polish Corridor, because then

Germany could choke off Polandís access to the sea. Furthermore, even a narrow

German corridor through Polish Corridor would mean putting Polish people under

German rule. (Many still remembered the heavy-handed Germanization policies in

former Prussian, now western Poland.)

On January 26, 1939, Ribbentrop paid

an official visit to Warsaw to

celebrate the fifth anniversary of the Polish-German Declaration of

Nonaggression. of Jan. 26, 1934. However, his real objective was to secure

Beckís agreement to the proposals which he and Hitler had made earlier. He also

tempted Beck with vistas of Polish expansion into the Soviet Ukraine, even as

far as the Black Sea, but Beck did not take up the offer. Finally, they agreed

that neither country would act unilaterally if the League of Nations withdrew

from Danzig.* Nevertheless, German leaders still hoped to isolate

Poland so that the Polish government would finally accept their

"reasonable" proposals. *

*[On German-Polish relations, Polish

and British policy toward Poland in the period October- 1938 - end January

1939, see Anna M.Cienciala, Poland and the Western Powers, 1938-1939. A

Study in the Interdependence of Eastern and Western Europe, London,

Toronto, 1968, ch.V. For an updated study including the Forster-Burckhardt

conversation, see same: "Poland in British and French Policy in 1939:

Determination to Fight or Avoid War,?" Polish Review, vol. XXXIV,

no. 3, New York, 1989, pp. 199-226, reprinted with some abbreviations in

Patrick Finney, ed., The Origins of the Second World War, London, 1997.]

III. Toward the British Guarantee

of Poland.

1. In December 1938 and again

February 1939, rumors reached the British government of Hitlerís alleged plans

to attack Holland, Belgium, and Switzerland, and bomb London at the same time.

In fact, these rumors were planted by the secret German "Resistance"

to Hitler led by Dr .Carl Friedrich Goerdeler (1884-1945, mayor of

Leipzig 1930-37), which was supported by some German generals, foreign ministry

officials and diplomats. In summer 1938, they secretly proposed to the British

government that they would overthrow Hitler if he provoked war with the Western

Powers. However, there was no war, so there was no attempt to overthrow Hitler.

Now, they advised a firm British attitude toward Hitler to prevent war

- but they wanted British agreement to Germany keeping Austria and the

Sudetenland as well as regaining Danzig and the Polish Corridor from Poland.

However, the British government did not take up the offer because

it still hoped for a negotiated settlement with Hitler.

2. On the night of March

14-15,1939, Hitler sent the German army into the Czech lands of

Bohemia-Moravia. A Czech-Slovak dispute was his pretext for this

attack. He also told the Slovak leaders to demand independence under his

protection - or he would give Slovakia to Hungary. He summoned Czech

President Emil Hacha (1872-1945) to Berlin, and threatened to bomb

Prague if Hacha did not ask for German "help." Hacha did so, Hitler

sent in German troops, and announced a German "protectorate"

over Bohemia-Moravia, as Slovakia declared its "independence."

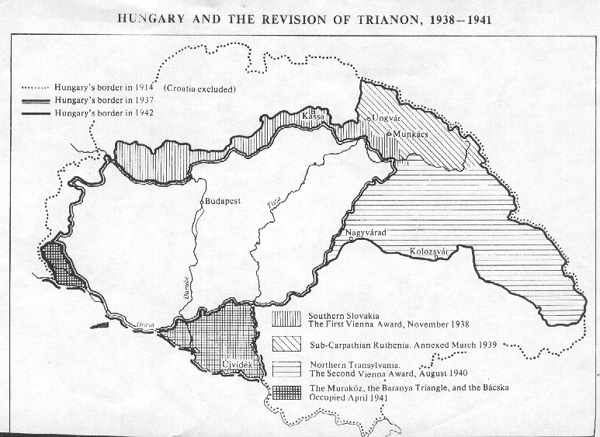

Hungary took her chance to occupy the rest of Subcarpathian

Ruthenia, thus creating a common border with Poland. (On November 2, 1938, Hungary had received a slice of

southern Slovakia and western SCR in the Vienna Award, agreed by Hitler

and Italian Foreign Minister, Count Galeazzo Ciano ,1903-1944, For. Min.

1936-43.)

Hitlerís occupation of the Czech

lands provoked outrage in Britain. Many saw it as proof that his word could not

be trusted and public opinion demanded the government take a firm stand. Still,

Neville Chamberlain proclaimed in Parliament that while he regretted

Hitlerís action, the French and British guarantees, promised to

Czechoslovakia at Munich, did not come into play because Czechoslovakia had

disintegrated in an "internal crisis." He said he would still pursue

his policy of seeking peace.

However, on March 16-17, the Romanian ambassador in London, Virgil V. Tilea,

informed the British government that Romania had received a German ultimatum to

sign an agreement with the Reich that would make it a German satellite. Tilea

may have done this on his own initiative so as to provoke a British guarantee

to Romania without implicating King Carol, but it is also possible that he had

the King's consent. (In fact, the Germans demanded the subordination of the

Romanian economy to their needs and a treaty to this effect was signed on 23

March.) Tileaís news, which spread fast in London, increased the pressure on

the British government to do something to stop Hitler. Therefore, Halifax persuaded

Chamberlain to insert a warning to the Fuhrer in the prepared speech he

delivered in Birmingham on March 17. The Prime Minister said that Britain

would not be passive if one power tried to dominate Europe.

On March 18, the British Cabinet decided to propose a declaration

by Britain, France, Poland and USSR that they would "consult"

together if there was a threat of further German aggression. On March 19, at

the insistence of the French ambassador in London, the wording was changed to consult

together on taking action.

That same day, the Soviet government proposed a conference of the same

states to meet in Bucharest to consider what they should do. It is

still unknown what Stalin wanted to gain by this proposal, but in view of his

deep distrust of Britain and his previous hints to Hitler about a nonaggresion

pact in 1935-1936, it is posible he intended the conference to put

pressure on Hitler to come to an agreement with the USSR. Whatever the case may

be, the British government distrusted the Soviets and did not want to provoke

Hitler. Furthermore, the British Dominions as well as many neutral countries

opposed a western alignment with the Soviet Union. Therefore, the Soviet

proposal was politely rejected and Britain stuck to the declaration on

consultation.

On March 22, Hitler annexed Memel (

Lith. Klaipeda) the mainly German-speaking port city of Lithuania and the

surrounding region. Hitler had gone there aboard a German warship. (He was so

seasick that he vowed never to set foot on a ship again.) Poland feared that he

might annex Danzig, so a partial mobilization was carried out the next day in

Polish Pomerania (Corridor) to warn him off. Hitler was angry, but he still

hoped to persuade the Poles to grant his demands peacefully.

Meanwhile, the Polish government

had rejected the declaration on consultation proposed by Britain,

on the grounds that if it signed along with the USSR, this might provoke a

German attack on Poland. The real reason, however, was deep Polish distrust of

the Soviet Union. But Foreign Minister Beck made a counter proposal. On March

22, he told the British Ambassador in Warsaw, Sir Howard Kennard,

why Poland would not sign the declaration; at the same time, he proposed

a secret Anglo-Polish agreement on consultation. The Polish

Ambassador in London, Edward Raczynski (1891-1993, Ambassador London,

1934-45, and briefly P. For. Min. in WWII, later president of the Polish

Government- in- Exile) made this proposal to Lord Halifax two days

later, on the afternoon of March 24. Halifax received it well and mentioned

the possibility that a British-Polish mutual assistance agreement might be negotiated

later.

That same day in the late afternoon or evening, Beck told a group

of high foreign ministry officials in Warsaw that Poland had to draw the line.

He said Danzig was a symbol, but also involved vital Polish interests. He said

that Poland was no longer isolated. (Which suggests that he might have learned

of the Halifax-Raczynski conversation, although Amb. Raczynski wrote

Cienciala -- in answer to her question about this --that there would not have

been enough time to decypher the report he sent to Warsaw after he seeing

Halifax.)

On March 25, Beck told German ambassador in Warsaw, Hans Adolf

von Moltke, that Poland could not accept the German proposals received on 21

March, ( a repetition of the previous German demands). Then he instructed Lipski

to tell Ribbentrop that Poland could not agree to the proposals. Lipski delivered this message to Ribbentrop on March 26. Meanwhile, the day before, on March 25, on hearing of

the Polish refusal, Hitler had issued a directive to the head of the German

army, General Wilhelm Keitel. Hitler said he did not want to drive Poland into

the arms of Britain. However, as soon as an opportunity arose, he would crush

Poland so badly that she would not play a role in European politics for decades

to come. He planned to annex western Poland, ( more or less the

territory of Prussian Poland in 1914), whos Polish population was to be

"evacuated" and resettled elsewhere. For the time being, however,

Hitler wanted to prevent an Anglo-Polish rapprochement. It is hard to see how

British historian A.J.P.Taylor (1906-1990) could claim the directive

showed that "Hitlerís objective was alliance with Poland, not her

destruction." *

[ A.J.P.Taylor, The Origins of

the Second World War, London, 1961, p. 210.]

The British Cabinet considered what

should be done, and the Cabinet Foreign Policy Committee discussed

the problem on March 27.Chamberlain said Polandís

attitude was uncertain as to helping Britain and France defend Romania

if she were attacked, but Poland was absolutely necessary to create a

"second front" against Germany in the East. Also, Poland might buckle

and accept Hitlerís demands, thus lining up with Germany... For these reasons,

he favored giving Poland a unilateral guarantee. Halifax

said that France and Britain could not prevent Poland and Romania from being

overrun, but Chamberlain responded by saying that the Western Powers could

divert some German forces by holding the Maginot Line. Finally, it was

agreed to give a unilateral guarantee to Poland in order to deter

Hitler from further aggression, but without setting a date when it should be

given.

Two days later, on March 29, Ian

Colvin, the Berlin correspondent of the News Chronicle arrived in

London with the "news" that Hitler was about to attack Poland at any moment.

Colvin had heard this from some members of the German "resistance"

who wanted to push the British government into taking a firm stance, frighten

Hitler, and thus prevent him from leading Germany into another war with the

Western Powers, which they believed she would lose again. In fact, Hitler had

not yet set a date for attacking Poland and the "proof" of attack

that Colvin brought -- that is supplies sent to the German troops stationed

near the Polish border -- was not at all new for the British War Office had

known of it for some time. Nevertheless, with rumors flying around London, that

evening, Chamberlain "agreed to the idea of an immediate

declaration of support of Poland, to counter a quick putsch by Hitler."*

*[Note by Alexander Cadogan, Wed.,

29th March 1939: The Diaries of Sir Alexander Cadogan O,M.

1938-1945, edited by Charles Dilks, London,1971, p.165].

Thus it was that on March 30,

Halifax asked Ambassador Raczynski whether Poland would

accept a British guarantee of her independence, and Ambassador Kennard

transmitted the same question to Beck in Warsaw. The Polish Foreign Minister

accepted the proposal at once. It should be noted that he had

rejected the German demands on March 25, five days before he was offered the

British guarantee.

What Beck did not know

was that the British Cabinet decided the guarantee of Polish independence was

conditional on Poland not being "stupidly obstinate" over Danzig and

relations with Germany in general, also on Poland actually fighting to defend

her independence. Furthermore, at noon on March 31, Chamberlain told the

British Cabinet that Britain would decide if and when Polish independence was

threatened.

On the afternoon of March 31,

Chamberlain read a statement in the House of Commons. He first said, at

great length, that the British government believed every dispute could be

negotiated. In the meanwhile, if Polish independence were threatened and Poland

resisted with all her forces, Britain would do all in her power to help Poland,

and France would do likewise.

However, this was not the end of

appeasement. The British guarantee of Polish

independence was meant to deter Hitler from further aggression and persuade him

to obtain what he wanted from Poland by negotiation. On April 1, (All

Fools' Day),Geoffrey Dawson (1874-1944), the editor of the London Times,

published an editorial saying the guarantee did not apply to Polish

frontiers, but to Polish independence. In his diary, he noted that

Halifax and Chamberlain agreed "this was about right."

Polish Foreign Minister Beck,

who was about to depart for London, issued a strong protest and even threatened

to cancel his trip, but the Foreign Office assured ambassador Raczynski

that the editorial did not reflect British policy (!) Beck visited

England on April 4-6, and succeeded in changing the unilateral British

guarantee to Poland into a secret, provisional mutual assistance agreement

between the two countries.*

*[For the British guarantee to

Poland and the provisional agreement of April 6, see: Anna M.Cienciala,

"Poland in British and French Policy in 1939," Polish Review,

no. 3, 1989, cited earlier; slightly abbreviated version in Patrick Finney,

ed., The Origins of the Second World War, London, 1997, pp. 413-433.].

IV. The Path to War: From the end of

March to August 1939.

There are several threads to follow

in this period: Polish-German Relations, Polish-French Relations,

Anglo-Polish Relations, Anglo-Soviet and German-Soviet relations, Anglo-German

Relations, also Anglo-French guarantees to Romania and Greece. These

threads were all inter-related, but for the sake of clarity, they will be

discussed separately.

1. Polish-German

Relations.

Hitler reacted to the Anglo-Polish rapprochement in a speech to

the Reichstag on April 28. He abrogated the Polish-German

Declaration of Nonaggression of January 1934, as well as the Anglo-German Naval

Agreement of June 1935. He listed German demands on Poland publicly for the

first time, said that Poland had rejected them, and stated that he would never

offer them to her again.

Beck gave the Polish reply in a speech to the Polish

Parliament on May 5. He declared that Poland wanted peace - but not any

price, and she would not allow herself to be pushed away from the Baltic Sea.

Poland, he said, was ready to negotiate with Germany, but only on an acceptable

basis. He stated that Poland wanted peace - "but not at the price of

honor." (He meant it would dishonorable for Poland to give up her

independence without a fight). Polish attempts to renew conversations with

Germany failed.The head of Beckís Cabinet Office, Michal Lubienski

travelled to Berlin later in an attempt to see Marshal Goering -- known

to favor a peaceful settlement with Poland --but the Marshal would not see him.

Whatever Lubienski was to propose at this time - and it may have been

the condominium project - Hitler did not want to listen.

Nevertheless, Beck hoped

almost to the end that Hitler would step back from the abyss of another

European war, and that British support would enable Poland to negotiate a

compromise settlement with Germany on Danzig. Also, British pressure on

Beck to do this was intense. There are indications that as late as July-August,

Beck considered the idea of a Polish-German "condominium" in Danzig

(which a Castle Conference had decided not to pursue in January), and it is

known that a project for dividing the territory of the Free City between Poland

and Germany was drawn up in the Polish Foreign Ministry for possible use. There

was also a compromise project for a German highway through the Corridor, but it

was to run through the southern part of the region which was home to many

Germans. These projects show that the Polish govt. did consider a compromise

possible, but there is no evidence that there was any interest in Berlin in

anything but full Polish acceptance of Hitler's demands..

2. Franco-Polish Relations and

the question of French and British military aid to Poland.

In the British guarantee of March 31

-- which was a joint one with France --and as well as in the secret British-Polish

provisional mutual assistance agreement signed April 6, 1939, Britain

had promised to help Poland "with all the means in her

power." In the secret interpretive protocol attached to that

agreement, the British recognized that a German attack on Danzig would be a

threat to Polish independence. (The P. govt. maintained that there could be no

German attack on Danzig without an attack on Poland as well. ) France was also

bound to aid Poland by the military convention of March 1921. However, the

Franco-British military general staff talks which took place in London in April

1939, ended with a secret agreement that if Poland were attacked by Germany,

France and Britain would adopt a defensive strategy.

Despite this agreement, in the Franco-Polish

protocols on implementing the old military convention signed in Paris on May

19, 1939 the French side stated that if Germany attacked Poland,

France would start bombing Germany, and after 15 days (the time needed for

French mobilization), the French army would launch a grand offensive against

Germany. The Poles were to fight so as to delay the advance of German troops

and hold out until the French attacked in the West. If France was attacked by

Germany, Poland was to attack her in the east.

It is unlikely that the French

general staff really believed that French commitments to help Poland would be

honored. It seems they assumed from the beginning that Poland should be

encouraged to fight as long as possible in order to win time for France, which

is what General Gamelin said at a Franco-British conference in September. In

any case, no plans for a grand offensive against Germany were made.

Furthermore. French Foreign Minister Bonnet made the ratification of the

military protocols of May 19 dependent on the signing of the political protocol

interpreting the Franco-Polish alliance, for he did not believe that Britain

would go to war over Danzig. The political protocol was not signed until

September 4, three days after the German attack on Poland, but no grand French

offensive against Germany took place. Gamelin explained later that the French

army had to take measures against a possible Italian attack.

The Polish general staff, for its

part, believed that the military protocols signed in Paris on May 19, meant

that the French had given up their defensive strategy of simply manning the

Maginot Line, and would attack Germany in the West if the latter attacked

Poland. They expected the French to attack the unfinished German fortifications

called the Siegfried Line. This seemed logical, for such an attack would divide

the German armies, while abandoning Poland would mean the Germans could later

launch all their forces against France when they were ready. But the Poles did

not realize the depth of the French military leadersí defensive psychology. They always thought of the terrible French losses in WW I,

and of the fact that a generation of potential fathers and recruits had

perished in the war.

3. Anglo-Polish Relations.

Despite the provisional

Anglo-Polish agreement on mutual assistance (April 6), British policy was still

aiming at a negotiated Polish-German agreement . On May 22-23, Halifax

visited Paris. He told Daladier and Bonnet that he hoped Danzig

would become a Free City in Germany, and that the Vatican would help negotiate

a Polish-German agreement on the Corridor at the right time. Nevertheless, the

British encouraged the Poles to believe that Britain would help if Germany

attacked.

In May, Anglo-Polish air staff talks took place in Warsaw.

The British officers strongly implied that if Poland were attacked and the

Germans bombed Polish military objectives, the British would bomb the same in

Germany. If the Germans bombed Polish civilian objectives, the British would

consult with the French on what action to take.

In July, General Sir Edmund Ironside, the Inspector General

of British Armed Forces, visited Warsaw. His main objective was to secure clear

answers from Polish military and political leaders on just how they would react

to a crisis over Danzig, which was then being filled with German troops -- who

arrived as tourists -- and the city was being armed to the teeth by Germany.

The Poles told Ironside that they would react in proportion to the threat. They

said that if Danzig was declared part of Gernany without a German attack on

Poland, they would protest. But they also said they believed any German attack

on Danzig would be accompanied by an attack on Poland. Despite the nature of

Ironside's questions, the very fact that he visited Warsaw, and was known to be

friendly to Poland, gave the impression of British determination to help the

Poles in case of war.

At this time, in July 1939, the

Polish military gave the British and French military an "Enigma" typewriter

each. These had been constructed on the basis of work by three Polish

mathematicians who had broken the German military "Enigma" code. The

Polish breakthrough -- aided by the French --led to the later development of

code-breaking machines by British code breakers working in the famous Bletchley

Park and the development of "Ultra," the secret name for the

intelligence produced by breaking German codes. It was to be the Western

Allies' secret weapon against Hitler.

In summer 1939, there were

Anglo-Polish negotiations for a large British loan to help Polish rearmament. The loan would provide credits for Polish purchases in

England. However, the British Treasury adamantly opposed this, and the War

Office did not have arms to spare for the Poles. Finally, the British government

agreed to give Poland a loan of 8 million pounds for buying British war

equipment. Most of this went to buy British planes -- to be sent by sea from

French ports to the Black Sea ports of Poland's ally, Romania -- but they were

shipped off too late to help Poland, and turned back.

For the whole period from end March to the outbreak of war, the British exerted

constant pressure on the Polish government not to do anything rash against

Germany, and to seek a negotiated compromise with Hitler.

4. Franco-British guarantees to

Romania and Greece.

On April 7, Italian forces invaded

Albania. This meant an Italian threat to

Greece, while Romania seemed threatened by Germany. (On March 23, a

German-Romanian treaty was signed subordinating the Romanian economy to German

needs). Therefore, the British and French governments now guaranteed the

independence of Greece and Romania. However, no military preparations were made

to implement the guarantees, so they were meant to deter Mussolini and Hitler

from moving against those countries. Romanian oil refineries and agriculatural

produce would help Germany counter the effects of an allied naval blockade,

while a Greece free of German domination was important for British forces and

naval bases in the Mediterranean. The guarantees were meant to prevent German

domination of these countries.

5. Britain, France and the

USSR - the Play for Germany.

France was an ally of the Soviet

Union since 1935 (ratified 1936), and the French government desperately wanted

to turn this into a triple alliance with Britain on the lines of World War I. Chamberlain

and his Cabinet distrusted Moscow but finally decided in late May to seek an

alliance with the USSR in order to deter Hitler from aggression.

Stalin is known to have viewed Britain as the number one enemy of

the USSR, so he distrusted British intentions but Foreign Commissar Maxim M

Litivinov probably had a genuine desire for a Soviet alliance with London.

Historians differ in their interpretations of Litvinov; some believe he worked

for collective security in 1934-38 and then for a Soviet alliance with the

Western Powers because this was Stalin's policy; others believe that Stalin

really aimed at a deal with Hitler at least since 1935, if not earlier, and

used Soviet apparent interest in collective security and later an alliance with

France and Britain, in

order to push Hitler into a deal with the USSR. Whatever the case may be,

Stalin dismissed Litvinov in early May 1939 and some historians see this as

indicating a step toward Soviet agreement with Germany. Indeed, a

comparison of German foreign policy documents available in print since the

1950s, with Russian foreign policy documents published in 1992, indicates that

in 1939 Stalin was far more interested in a nonaggression pact with Hitler -

which he had suggested to Berlin in 1935 through Maxim Litvinov and in 1936

through his special envoy, David Kandelaki - than in a triple alliance with

Britain and France.

It is true that the British at first wanted only a Soviet commitment to help

Poland and Romania in case they were attacked by Germany, and this looked to

Stalin like placing the whole burden on the USSR. Stalin also saw British

guarantees to Poland and Romania as aimed against the USSR. (The two countries

had a defensive alliance to support each other in case of a Soviet attack on

either of them.) After a while, however, the British and French proved willing

to negotiate an alliance and military convention with the Soviet Union. The

sticking point in late summer 1939 was Moscow's insistence that the western

powers accept its definition of "indirect aggression,"

that is, the right to enter Estonia or/and Latvia, if the Soviets

perceived that either country even changed its government and/or policy so as

to threaten the USSR. What the Soviets had in mind was, of course, a

German invasion of their territory through these countries, which signed

nonaggression pacts with Germany in June. France and Britain proposed a

far-reaching compromise in an exchange of letters, which would grant the

Soviets what they wanted without putting this in the public text of the treaty,

but this was not enough for Stalin.

In view of Russian claims, made in

2008-09, that Stalin had no choice but sign an agreement with Hitler in late

August 1939, also that Poland had a secret agreement with Germany against the

USSR signed in 1934, and that France and Britain wanted Hitler toattack the

USSR, this whole issue needs to be set out clearly.

First of all, Poland had signed a

non-aggression treaty with the USSR in 1932, and after signing the Declaration

of Non-Aggression with Germany in late January 1934, For. Mn. Beck travelled to

Moscow in Feb. to sign a 10-year extension of the non-aggression treaty with

the USSR. Secondly, there was no secret Polish-German agreement against the

USSR. Thirdly, it is clear that Stalin was very interested in reaching an

agreement with Germany.

The Soviet leader, in fact,

authorized Georgii Astakhov, the Soviet charge d'affaires in Berlin .

(Ambassador Merekalov left for Moscow in May, )to conduct secret talks with the

Germans .* The ostensible goal of these talks was the renewal of the

German-Soviet Trade Agreement of 1935 which had lapsed in 1938, and which was

very important for the Russians. However, Astakhov kept on hinting at Soviet

interest in a political agreement. In fact, Foreign Commissar Vyacheslav

M. Molotov (1890-1986, Foreign Commissar May 1939-1955), first

mentioned this interest to the German Ambassador in Moscow, Count Friedrich

Werner von der Schulenburg, in May, and confirmed it to him in early

August. (Molotov succeeded Litvinov in early May, indicating a change of

direction in Soviet policy. Litvinov was Jewish; therefore some foreign

observers saw this as a move toward Berlin.)

*[Georgii A. Astakhov,1897-1942, Soviet charge d'affaires in Berlin 1938-40;

arrested in USSR, Dec.1939, he was either shot or died in a Soviet forced labor

camp in 1942.]

Aside from the many secret

indications of Soviet interest in a political agreement with Germany, there

were also "leaks" of British and Franco-British proposals to

Moscow. These documents were passed to the Soviet Embassy in London,

which sent them on to the German Embassy there, which in turn telegraphed them

immediately to Berlin. The documents were provided by a Soviet mole in the

Foreign Office Code Room,Ret. Captain John - or John Herbert - King, an

Irishman who hated the English and needed money. * This procedure of

informing the Germans of British proposals indicates Soviet pressure on Berlin

to come to an agreement with Moscow. At the same time, of

course, it meant that Molotov always had advance notice of what

the British ambassador, or the latter together with the French ambassador, was

going to tell him.

*[See: Donald Cameron Watt,

"Francis Herbert King. A Soviet Source in the Foreign Office," Intelligence

and National Security, vol. III, no. 4., London, 1988, pp. 62-82. He is

elsewhere named: John Herbert King].

We should also keep in mind that

five highly placed British civil servants were Soviet "moles"

in the British establishment. Among them was Kim Phliby, who was to become the

head of British military intelligence, the MI5.

The British govt., for its part -

especially Prime Minister Chamberlain --, was pursuing a policy of covert appeasment,

and Stalin may well have known about it. In fact, there were some secret

Anglo-German talks. These were leaked to the British press, where a report

appeared on July 22, 1939. Chamberlainís closest adviser at this time, Sir

Horace Wilson, actually proposed to the Germans in early August that

Britain and Germany conclude a non-aggression pact, after which Britain would

drop her guarantees to Poland, Romania and Greece. (He may have done so in

July, but no British document on this has survived.) However, Hitler sent no

answer until he knew he would have a pact with the Soviets. He then

insisted on having his demands on Poland met first, and only then entering into

negotiations with Britain for a general settlement.

In early August, a Franco-British military

delegation - or rather two delegations which worked together - set out for

Leningrad (formerly and now again Petersburg) on

a slow merchant ship.* This,

plus the lack of a prominent British military or political figure with full

powers, was criticized at the time and since as indicating a British lack of

interest in the Soviet alliance. General Ironside, Inspector General of

British armed forces, would have been the logical senior military figure to

send, but he was ineligible because he had commanded British and Polish troops

in northern Russia against the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War (1918-21).

The French delegation (France was already allied with the USSR in 1935) had

full powers to negotiate, but the British did not.The British lack of full

powers was due to the British government's assumption that a military alliance

would be concluded when agreement was reached on the issue of "indirect

aggression" (Soviet demands reg. Baltic States), or, if possible, that

both be reached at the same time. Thus, Foreign Secretary Halifax could not

have gone to Moscow without some basic agreement being reached first, but this

was not the case. (When Ribbentrop went to Moscow later, basic agreement had

been reached and only the details had to be worked out).

*(The slow travel by ship, which is

often criticized as foot dragging by the British and French,was due to the fact

that the joint delegation could not travel by the most direct route to Russia,

that is, through Germany (then Poland), while sending the delegation on a

warship was considered "provocative" to Germany. Finally, the British

navy only had two Sunderland Flying Boats at the time, and did not want to put

them at risk.)

It can be argued that the British

and French leaders were not really eager to undertake military obligations to

the USSR. Indeed, they aimed above all at an alliance and military convention

with Moscow in order to deter Hitler from attacking Poland and setting

off a possible European war. However, these considerations are immaterial

because in early August Molotov had already told the German

Ambassador in Moscow that the Soviet government insisted on the conclusion of a

political agreement, and, by the time the the Franco-British-Soviet talks began

on August 12, Stalin knew that Hitler was willing to conclude an agreement with

Moscow which recognized Soviet interests in East Central Europe, particularly

in Poland.

Furthermore, Stalinís

instructions to the head of the Soviet delegation, Marshal Kliment Y.

Voroshilov (1881-1969), dated August 7, show great distrust of the British

and French. He said that even if the western delegations revealed their

countriesí military plans, Voroshilov was to demand the passage of Soviet

troops through Poland Romania in case of war as the absolute Soviet

condition for signing the alliance. *

*[Dokumenty Vneshnei Politiki,

1939 god. Kniga 1, (Documents on Foreign Policy, the Year 1939, book

1,Moscow, 1992), doc. no. 453, p. 584]

This demand, which had not been

raised earlier in Anglo-Soviet negotiations (proceeding since May), was made by

Voroshilov at the first full meeting of the combined delegations on 12 August.

When the Soviets suspended negotiations on 17 August --ostensibly to allow the

Western Powers to secure Polish and French agreement to the entry of Soviet

troops to Poland --the French and British representatives in Warsaw tried hard

to get Polish agreement. The Polish government and high command refused, saying

they did not believe the USSR would fight Germany, and that once Soviet troops

entered Poland - they were unlikely to leave.

In any case, it is clear that Stalin

and Molotov were determined to make a deal with Hitler, and the main points

were agreed on two days earlier, on August 15. While the military talks with

the French and British were suspended, Hitler asked Stalin to receive

Ribbentrop by August 23, and Stalin agreed. On August 22, the German press

announced the signature of the Soviet-German Trade Agreement, that the

Nonaggression Pact would be signed the next day, and Ribbentrop would travel to

Moscow. On the night of August 23, the Polish government said they would not

oppose the discussion of the passage of Soviet troops by the general staffs in

Moscow, but Ribbentrop was then negotiating with Stalin. Even if the Poles

had agreed earlier, it is most unlikely that Stalin would have traded an

agreement with Hitler for one with the Western Powers specifically to to help

Poland if it was attacked by Germany. *

*[ For a discussion of the

diplomatic negotiations, secret talks, and Polish foreign policy in 1939, See

Anna M.Cienciala, "When did Stalin Decide to Align with Hitler and was

Poland the Culprit?", in M.B.B. Biskupski, ed.,Ideology, Politics

and Diplomacy in East Central Europe,

(University of Rochester Press,

2003), pp. 147-227].

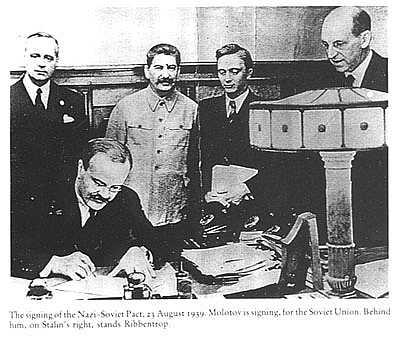

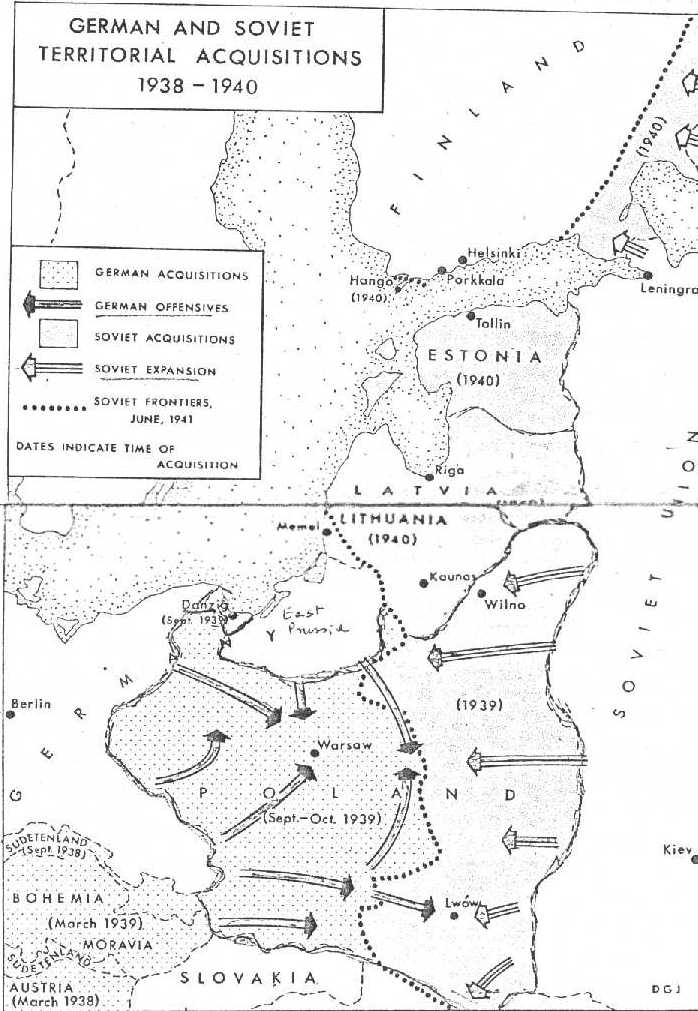

German documents show that the Secret

Protocol to the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact was worked out at the

Kremlin by Ribbentrop and Molotov and their aides during the night of August

23-24. They agreed that Poland would be

divided down the middle, so that the Soviets would even have the right bank or

eastern half of Warsaw (The city is divided by the Vistula river into left

(eastern)and right (western) bank Warsaw.) Germany also recognized preponderant

Soviet interest in the Baltic States of Finland, Estonia, and Latvia, with the

northern frontier of Lithuania (that is, with Latvia) demarcating the

German and Soviet spheres of interest in that region. The Germans also

recognized Soviet interest in Bessarabia. [Part of the Russian Empire to

1918, then part of Romania, now Moldova].*

*[Documents on German Foreign Policy, ser. D, vol. VII, London,

Washington, 1956, doc. nos. 228,229. No Russian record of these negotiations

has been published].

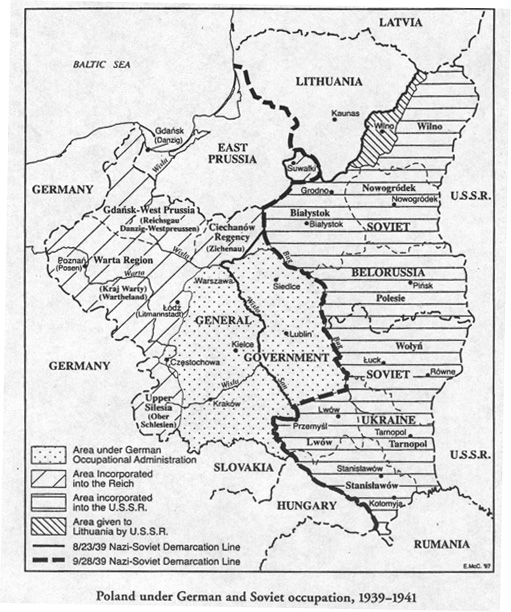

[from

R.Watt, Bitter Glory].

[from: Tadeusz Piotrowski, Poland's Holocaust. Note the two different German-Soviet lines of Aug. 23 and

Sept. 28, 1939 in Poland and Lithuania.

All Soviet authorities denied the

existence of the Secret Protocol until end December 1989, when it was disclosed

that a "verified copy" had been found in the Soviet archives, and the

Secret Protocol was condemned by the freely elected Supreme Soviet.

The original Russian copy was "found" in the Kremlin

Presidential Archives somewhat later. Only the Non-Aggression Pact was known in

1939, but it shocked world opinion, especially communist party leaders outside

the USSR who had been propagating the anti-fascist line.

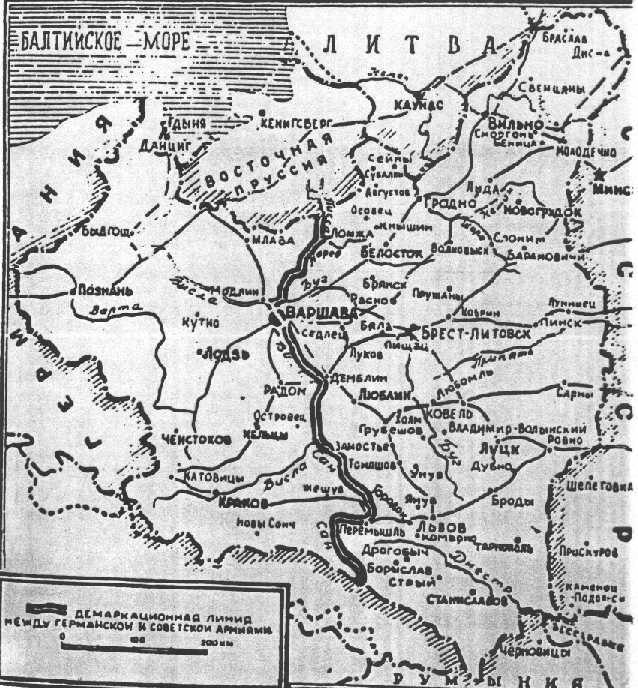

It is worth noting that the Aug. 23

German-Soviet "demarcation line" in Poland (including the addition of

the Pisa river) was actually shown on a map printed in the Soviet paper Pravda

[Truth] on 23 September 1939 (see below), probably as a reminder to the

Germans, who had already gone east of it. Interestingly enough, in the Secret

Protocol Stalin was willing to leave Lithuania to Germany. In the Soviet-German

Treaty of Sept. 28, Hitler recognized Soviet dominant interest in almost all of

Lithuania. In exchange, Stalin gave up a part of Poland gained in the Secret Protocol

and agreed to pay Germany several million dollars.

The

German-Soviet "demarcation line" in Poland (according to the Secret

Protocol of Aug.23, 1939, amended on September 22 to include the Pisa

river).

Pravda, Sept. 23, 1939.

When the Nazi-Soviet Pact gave

Hitler a free hand to attack the Poles, the British government decided to

conclude a Mutual Assistance Treaty with Poland, signed in London on August

25. The timing of the signature, 5 p.m., was set to coincide with the

delivery of a letter from Mussolini to Hitler - which the British

ambassador in Rome had encouraged him to send - saying that Italy was not ready

for a war with the Western Powers unless it received enormous amounts of raw

materials and arms from Germany. The combination of the treaty and the letter

made Hitler cancel his orders, given on August 23, for an attack on Poland to

start on August 26. However, the cancellation failed to reach a German unit on

the Polish-Slovak border, so it got into a fire fight with the Poles and

retreated.

Chamberlain and his Cabinet saw the

treaty with Poland as a deterrent to Hitler, for they still hoped for a

negotiated German-Polish agreement granting Hitler what he wanted. Therefore, Birger Dahlerus, a Norwegian businessman

and friend of Goering, shuttled secretly between London and Berlin in late

August. His mission was to persuade Goering and Hitler to work for such a

result. It was even agreed that Goering would pay a secret visit to England,

but Hitler cancelled it when he had the agreement with Stalin in hand.

On August 27, Chamberlain told the Cabinet that Poland could at most accept the

return of Danzig to Germany and a German extra-territorial highway and railway

through the Corridor. He said this despite the fact that the Polish government

had always viewed this solution as unacceptable. Therefore, Chamberlain was

expressing his opinion, and not that of Britainís ally.

Hitler made an apparent ploy for peace, but German armed forces

had orders to attack Poland on September 1, so his aim was to place the blame

for war on the Poles. At midnight on August 29, Ribbentrop quickly read

to the British Ambassador, Sir Nevile Henderson, a list of terms for Poland

which would allegedly ensure peace. Danzig was to return to Germany

but Poland would keep its rights there; there was to be a plebiscite in the

Polish Corridor, but all Poles who were born or settled there since early 1919

would have no vote, while all Germans born, even if not living there, would. (Hitler

did not seem to realize that there was a Polish majority in this region

according to the Prussian census of 1910, see Lec. Notes 11, The Rebirth of

Poland). Poland would have guaranteed access to the sea. There would be an

exchange of minority populations between the two countries. If Poland accepted

these terms, Germany would agree to the British offer of an international

guarantee, but this would now include the Soviet Union. A Polish

plenipotentiary (with full powers) was to arrive in Berlin to accept these

terms by noon the next day.

The British Cabinet thought the

terms were "reasonable," except the demand for a Polish

Plenipotentiary which was too much like the Czech President Hacha accepting

Hitlerís terms in mid-March 1939; they feared outrage in British public

opinion. The British government had asked the Poles a few days earlier if they

were ready to negotiate, to which Beck said yes -- providing the terms were

not contrary to vital Polish interests, (which were: Danzig to continue

to exist as a Free City, and the Polish Corridor to continue to be part of

Poland).

At this time, on August 29-31, the Sir Nevile Henderson

exerted great pressure on Polish Ambassador Jozef Lipski to accept Hitlerís

offer. It is clear from British documents, that Henderson acted in

agreement with Halifax, though he exceeded his brief because he was openly in

sympathy with German demands. Sir Horace Wilson -- who shared their views --

told him to be careful on the phone because it was bugged by the Germans.

In Warsaw, the British and French

Ambassadors now pressed the Polish government not to proclaim

mobilization -- which was viewed as having triggered World War in 1914. The

Polish government agreed, but proceeded to mobilization by mail (post cards).

When Ambassador Lipski went to see Ribbentrop on August 30, he was presented

with Hitlerís demands. Ribbentrop asked the Ambassador if he had full powers to

sign. When Lipski said he had come to receive the German terms, Ribbentrop

ended the meeting. The German radio then broadcast Hitler's demands with the

comment that Poland had rejected them.*

*[For an account of these events, focusing on British and French policy,

see: Anna M. Cienciala, "Poland in British and French Policy in

1939..." in Finney, cited earlier].

It is clear that the conclusion of

the Nazi-Soviet Pact removed any fears Hitler may have had about risking a

European war by attacking Poland, and this seems to put the onus on Stalin.

Some historians have claimed-- as is the official Russian position today,

August 2009 -- that Stalin had no other choice because he had to obtain

security for the USSR, which faced the Germans in the West and was fighting the

Japanese in the Far East. This is the line followed by some Russian historians

and most Russian media today, along with charging Polish For. Minister Beck

with following a pro-German policy in 1939; some media even charge him with

being a paid Germana agent. These charges are designed to show that Stalin had

no choice but to go with Hitler; there is no explanation how and why a

pro-German Beck, or as a German agent, rejected Hitler's demands and secured

first, a British guarantee of Polish indeepence, and then an alliance with

Britain.

. Russian TV showed a film on Aug.

23,2009, claiming that Poland was in cahoots with Hitler and had even planned

to attack the USSR in tandem with Germany and Japan (!). The film also claims

that Poland had a secret agreement with Hitler, attached to the Jan. 26 1934

Polish-German Declaration of Non-Aggression, valid for ten years.There was no

such secret protocol. On the contrary, Poland had signed a Non-Aggression

Treaty with the USSR in July 1932 and Foreign Minister Jozef Beck travelled to

Moscow in Feb. 1934, where he signed a 10-year extension of the treaty.

The USSR did not offer an alliance

to Poland in 1939. Soviet Deputy Foreign Commissar V. Potemkin, told Beck on

May 10 that the Soviet Union would observe benevolent neutrality in case of

war. The Soviet ambassador, Sharonov, also stated around this time that Moscow

would consider asssistance to Poland if the latter asked for it. These statements were not equivalent to the offer of an

alliance to Poland, as some historians claim.

Another argument used by pro-Kremlin

authors is that of Soviet security. They assumes that it would be strenthened

by the seizure of eastern Poland and later the Baltic States so Stalin must

have aimed to control the main access routes into the USSR: the northern route through

the Baltic States and the southern route through western Ukraine, then S.E.

Poland; the Polesie marshes lay inbetween. (The the Soviet government drained

the marshes after World War II.) In fact, however, the new German-Soviet

frontier of Sept. 28 1939 brought German armies that much closer to Moscow (see

Piotrowski map above). The Germans regained former eastern Poland in about two

weeks in June-July 1941, while also overunning the Baltic States. If they had attacked a couple of weeks earlier, Hitler might

have held a victory parade in Moscow. Stalin had done nothing since occupying

eastern Poland in September 1939, to prepare for the defense of these

territories. His worst error was refusing to believe the warnings sent by

Churchill and Roosevelt in spring and summer 1941, also his man in Tokyo,

Richard Sorge, that Hitler was prepring to attack the USSR. We may assume he

rejected these warnings because they did not fit his timetable for Soviet

readiness to fight Hitler, or/and he may have believed Hitler would not risk

such a war. We do not, however. know what Stalin was thinking because

theRussian documents, which might clarify the issue, remain inaccessible in

Russian archives.

It should be mentioned, that Soviet

military intelligence reported in late 1938 that Hitler was planning to attack

Poland next, and that his main goal was the destruction of the USSR.But no such

warnings came in 1939. As it happened, Hitler turned against Czechsoslovakia,

then Poland, but Stalin may have expected Poland to accept Hitler's demands and

become a willing satellite of Germany in an attack on the USSR.

The most balanced Russian statements

on the whole issue were made by Vladimir Ryzhkov (b.1966), who had

represented Barnaul, (Siberia) in the Duma in 1993-2007. He became head of the

Republican Party of Russia, which was refused registration for the elections of

2005. Ryzhkov sees responsibility for the outbreak of the war as shared by

France and Britain, although the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact also played a major

role. Nevertheless, the main responsibility if, of course, Hitler's.*

*(For Ryzhkov's statements on the

Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, see "Detrimental Denial," Moscow News,

no.32, 2009. Ryzhkov is now professor at the Higher School for Economics, and

chairman of the political organisation "Russia's Choice.").

Just ahead of the 70th anniversary

of the German attack on Poland in 1939, and on the eve of his own visit to

Gdansk, along with other statesmen for the celebrations, Russian Prime Minister

Vladimir Putin wrote an Open Letter to the Polish people, printed in Gazeta

Wyborcza, Aug. 31, 2009. He stated that the Russian Duma had condemned the

Secret Protocol to that Pact in Dec. 1989, and it was, of course, immoral. He

pointed out, however, that the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact should not be seen as

causing the outbreak of WW II. He said that the roots of the war went back

further, and pointed out the Munich Agreement of Sept. 28, 1938, in which

France and Britain had agreed to the cession of part of Czechoslovakia, the Sudetenland,

to Germany, while Poland took a part of Czechoslovakia (western Cieszyn/Teschen

Silesia). He mentioned the sad fate of Soviet prisoners of war in Poland in

1920 *and also mentioned the Versailles Treaty of 1919 ( a hint at German

resentment of losing Danzig and the Polish Corridor to East Prussia). He also

recalled that Poland had annexed a piece of Czechoslovakia in fall 1938.**

*[NOTE by Cienciala: Out of 100,000

Soviet Prisoners in Polish captivity in 1920, Polish and Soviet historians agreed

that 16-18,000 died of malnutrition and hunger (Russ. lang. book on Red Army

Men in Polish Capitivity, 1919-1920, published Moscow, 2004). About 40,000

returned home to Russia, while the rest either joined anti-Bolshevik forces or

found some kind of a living in Poland. While the Polish camp commanders can be

charged with not providing enough food and medication to the prisoners, we

should note that in 1920 there was general malnutrition as well as a typhoid

epidemic in Poland. Herbert Hoover's American Relief Administration (ARA) saved

the lives of thousands of Polish children. The ARA also saved many lives in

Russia, where famine raged at this time.]

Adam Michnik, the founder and editor-in -chief of Gazeta Wyborcza,

answered Putin in the same newspaper. He welcomed Putin's conciliatory

statements and hope for better Polish-Russian relations. He also pointed out,

however, that while the Polish annexation of (disputed) Czech territory was

immoral, the new Polish administration there did not shoot or deport any Czechs

in that area (as the Soviets did to Poles and others in Eastern Poland,

1919-41). As for the Soviet prisoners of war in Poland in 1920.Michnik stressed

the fact that none of them had been shot in the back of the head. ***

Putin's speeach on Sept. 1, 2009, at

the meeting of of several European leader in Gdansk,was much shorter and more

conciliatory to Poland Polish Premier Tusk spoke in the same spirit.

** As for the Versailles Treaty

solutions of the Free City of Danzig and the award of the predominantly Polish

Pomerania (Corridor) to Poland, these were compromises fair to both sides. Of

course , the Germans resented the separation of East Prussia from Germany, but

the predominantly Polish population of the Corridor could not be put back under

German rule. Communication with Germany was assured by six trains crossing the

Corridor every day while most of the bulk trade went by sea, as it had done

before the World War I.. It should also be noted that all German governments

before Hitler -- and at first, Hitler as well -- demanded revision of the

German-Polish frontier, which meant not only the return of Danzig and the

Corridor but all of former Prussian Poland to Germany. Hitler at least put

these demands on the back burner by agreeing to the Polish-German Declaration

of Non-Aggression of Jan. 26, 1934. See Lec. Notes 14a.]

As for the date of the Soviet attack

on eastern Poland , Sept. 17, if Stalin waited to see whether the French Army

would attack Germany in the West, it was clear by Sept. 16 that it would not do

so. He ordered the attack to take place

on Sept.13, but postponed it to Sept. 17 on being assured by the Germans that

they were about to take Warsaw. (In fact, it surrendered on Sept.27.)

As for the Japanese-Soviet conflict

in the Far East, it may have been a factor in Stalin's policy before 23As

August 1939, but by that time the Japanese forces involved in the Nomonhan area

were being beaten back by Army Commander (later Marshal) Georgy Zhukov,

and an armistice was signed on Sept. 16. Furthermore, the Soviet mole in Tokyo,

Richard Sorge (1895-1944), informed Stalin in summer 1939, on the basis

of his contacts with high Japanese officials, that Japan would not be ready for

war for another two years, and it was not planning to attack the USSR. (The Japanese finally arrested Sorge, but Stalin refused

Tokyos's offers of exchaning him for some Japanese officers, so he was executed

in 1944.)

Some historians believe that

Stalinís decision to line up with Hitler was most likely based on an alleged

key assumption of Soviet policy: that a war between the capitalist powers would

lead to their mutual exhaustion and therefore pave the way to the establishment

of communist governments in Europe, presumably under Soviet control.

Indeed, one can deduce as much from Stalin's statement to Georgii Dimitrov,

head of the Comintern (Communist International) on Sept. 17. According to

Dimitrov's diary, in early Steptember Stalin said the longer France and Britain

fought Germany, the better, and he would help both sides. Also, Poland was a

fascist state which oppressed the Ukrainians and Belarusians and there was

nothing wrong with gaining territory for the USSR and expanding Socialism. *

*(Diary of Georgii Dimitrov,

1933-1948, introd. by Ivo Banac, (Yale Univ. Press, 2003), entry for

Sept. 7, 1939.).

As for the argument that the

Ukrainians and Belarusians suffered under Polish rule, there is no doubt that

they resented it, but Soviet rule was much worse. Stalin forced

collectivization on Soviet peasants and used famine to break resistance in

Soviet Ukraine in 1932-33. This led to the death of an estimated 5 million

Ukrainians. There was famine in other parts of the USSR, but nowhere was it as

dreadful as in Ukraine. Many peasants, who lived on the Soviet side of the

border, fled to Poland.

We do know that Stalin was shocked

by the rapid defeat of France in May-June 1940. He seems to have expected a

longer stand off . Of course, in the short run the USSR would profit by gaining

territory which could be viewed as a buffer against German attack. but it

proved not to be such in 1941. Indeed, Stalin did not make use of the time he

had to strengthen hist western defenses against Germany. On the contrary, he

ordered the destruction of the old Soviet fortifications on the former

Polish-Soviet border, which would at least have held up some German forces, and

he did not build any new ones. Was he perhaps thinking of removing obstacles to

a future Soviet attack on Germany? No one can give absolutely sure answers to

questions about Stalin's policy in 1939 because the relevant Russian documents

are still inaccessible to historians.

6. The German Attack on Poland

and the Outbreak of World War II.

On September 1, 1939, several German

armies attacked Poland from the West, North and South-West. To justify this aggression, German

propaganda faked a Polish "attack" on the radio station in the Upper

Silesian town of Gleiwitz (now Gliwice, Poland) , and this was broadcast to the

world. (After the war, it was found that the SS - Security Police - had used

German political prisoners dressed in Polish uniforms, and murdered them after

the "attack" to eliminate witnesses. The sturdy, wooden radio tower

still stands in Gliwice toda).

The French and British governments

delivered warning notes

in Berlin on September 1,

stating that if the German army did not withdraw from Poland, they would

immediately fulfill their obligations to that country. At the same time,

however, the British government encouraged Mussolini to propose a great

power conference, this time including Poland, and the French government

supported this move. On September 2, Mussolini informed the British that he was

trying to get Hitler's consent, but thought he was unlikely to withdraw

his forces from Poland unless he first got what he wanted. Mussolini also said

that Hitler asked for time until midnight September 3, to answer Mussoliniís

proposal. Meanwhile, German armed forces continued their attack on Poland.

The British Cabinet met at 4 p.m.

September 2. Halifax reported

Mussoliniís information and proposed the deadline for Hitlerís answer to

the British and French notes be set at midnight September 3. The

Cabinet decided for midnight the same day, Sept. 2, but left the

"coordination" of French and British action to Halifax.

That evening, September 2,

Chamberlain spoke in the House of Commons and Halifax in the House of Lords. They

stated that if German forces withdrew from Poland, then the British government

would treat the situation as if nothing had happened, and would support

Polish-German negotiations, or a wider conference. They did not give a deadline

for Hitlerís answer to the British note.

The staid House of Lords, which

respected Halifax, heard him out in silence -- but there was uproar in the

House of Commons. Chamberlain was told that he must report to the House the

next day by 11 a.m. There was a revolt in the Cabinet too. Therefore, on the night of September 2, Chamberlain told

the French government that Britain had to act, and instructed Ambassador

Henderson to deliver a note to Ribbentrop the next day at 9 a.m. demanding an

answer by 11 a.m. Henderson did so, and the French ambassador delivered a note

demanding an answer by 5 p.m.

When there was no answer from Hitler

by 11 a.m. Setp 3, Chamberlain spoke on the radio stating that Britain was at

war with Germany. The French government stated the same at 5 p.m. Thus, the

German attack on Poland and Polish resistance brought about the outbreak of

World War II.

7. The German-Polish War,

September 1 - October 5, 1939.

The Polish General Staff, government

and the Polish people expected Britain and France, especially the latter, go

give them military aid, as per their agreements, by attacks against Germany in

the West. However, Poland received no help from the its allies. The French

manned the Maginot Line and made a few probing forays into West Germany, after

which they withdrew. General Maurice Gamelin (1872-1958),

Commander-in-Chief, Allied Forces, told the British on September 12, that he

had ordered the withdrawal of French forces from Germany [small forces had gone

a few miles forward], and that he would not attack Germany even if the Poles

resisted for three months -- because their task was to gain time for France. *

*[For source, see Cienciala in

Finney, cit above.]

The French and British had about

1,600 first line planes against 600 German planes in the West; they had 2,600

tanks against some 850 -- while about 1,600 were in Poland. About 100 French

divisions faced 26-30 German divisions, most of them manned by reservists; and

the Siegfried Line -- the German defense line in the west-- was still

unfinished. The two powers, had, however, agreed to be on the defensive if

Germany attacked Poland; they did not tell the Poles.

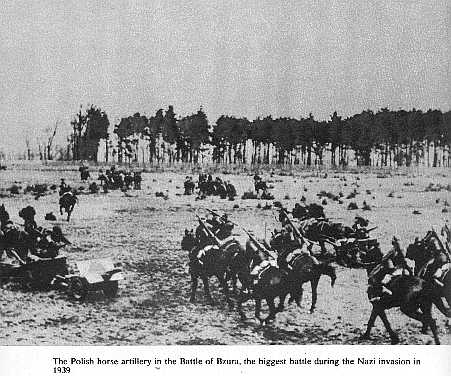

The Poles had about 400 planes, most

of them outdated, facing 1,800 German planes. They had about 300 light,

French-made tanks facing about 1,600 German tanks. A German warship pounded the

Polish munitions depot at Westerplatte -- just north of Danzig harbor-- where

the Polish garrison fought gallantly for 12 days. Other warships were pounding

Polish defenses on the tiny Hel peninsula west of Gdynia; the fortifications

there were the last to surrender to the Germans.

The German airforce did not destroy

most of the Polish planes on the ground, as is often stated in books about this

war. In fact, they had been camouflaged or moved elsewhere to prevent this from

happening. Most of these planes -- which were outdated in any case --were

destroyed in air battles. The German airforce did, however, wreak havoc with

the Polish rail and road network. It also attacked undefended towns and

villages. Indeed, Hitler had given orders to German airmen that they were

to show no mercy to the Polish population. The Polish government

appealed to the British to bomb Germany, but Lord Halifax finally told

Polish Ambassador Edward Raczynski that this would not be done, and

Poland must wait for allied victory.

In fact, British planes carried out

one raid on the German naval base at Wilhelmshafen, and made a few

desultory sorties over the Ruhr. They did no more than that, so people thought

this was to avoid German retaliation against London. In fact, British and

German air force experts knew that German bombers could not do carry havy bombs

to London, unless they flew from airfields in western France - as they were to

do in the Battle of Britain, 1940-41.

The Polish defense plan seemed strategically absurd: the Polish army was to try and

hold the whole length of the German-Polish frontier and retreat slowly when

forced to do so. But the Polish General Staff had two reasons for this

strategy;(a) they feared that giving up Western Poland with its industry and

Polish population in order to hold a defensible line on the Vistula, might lead

Hitler to offer peace negotiations to France and Britain , which might

recognize his conquests; (b) the Franco-Polish military protocols of May 19,

1939, stipulated that the Polish armed forces were to delay the German advance

along the whole front line until the French army was ready to attack Germany in

the West, that is, on the 16th day after the start of the German

attack (15 days for mobilization). The French airforce was to bomb Germany.

However, as stated earlier, the French had no intention to do so, or to launch

an offensive against Germany, so Poland was left to fight alone.

Finally, the retreating Polish High

Command planned to regroup its forces in south-eastern Poland, near Romania,

which was expected to receive French and British arms and planes to pass on to

the Poles. These plane, however, became inoperative once the USSR attacked

Poland on Sept. 17.

|

|

|

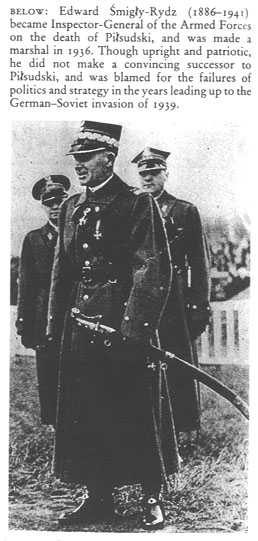

[pictures

and captions from: R.Watt, Bitter Glory - The Marshal is shown at

a parade, wearing a winter coat and sporting a dress saber].

7.The Soviet attack on Poland.

The Red Army entered eastern Poland

on September 17. Stalin and Molotov had resisted German pleas to march into

Poland after the German attack began, but it is clear from Russian documents

(available in 1989-90) that although the Soviet western military districts of

Minsk and Kiev were mobilized and the original orders were for them to attack

on 9 September, the attack was postponed to September 17.

No reason is documented for the delay. It may be that Stalin was waiting

for an agreement with the Japanese to end the fighting in the Far East, and

this took place on September 13 with the armistice signed three days later. Or

he may have waited to see what the French and British would do, particularly

the French, would attack Germany in the West; or he waited for the fall of

Warsaw to the Germans. Also, there were no signs of preparations for a French

offensive against Germany.

There was some difficulty in

agreeing on the text of the Soviet declaration justifying the Soviet move.

German and Russian documents show that Molotov at first proposed a statement

saying the Red Army was coming in to save its Ukrainian and Belorussian

brothers from the Germans, but this was unacceptable to the Berlin so it was

later changed to giving them security and the Polish people the chance for a

happier life (!) Finally, when the Germans informed Moscow on Sept. 16 that

Warsaw was about to be fall (it did not), Stalin and Molotov informed the

German Ambassador at 2 a.m. on September 17 that the Red Army would enter

Poland at 6 a.m. that day.

The Polish Ambassador in Moscow, Waclaw

Grzybowski (1887-1959, ambassador in Moscow 1937-39), was handed a note at

3 a.m. on September 17 by Deputy Foreign Minister Vladimir P. Potemkin

(1874-1946), who had summoned him to his office. The note, drawn up by Molotov

and sent also to all foreign diplomatic representatives in Moscow, stated that

since Warsaw had surrendered and the Polish government had ceased to exist

(neither of which was true), the Soviet government considered its treaties with