hist557 by anna m.cienciala is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. Based on a work at web.ku.edu.

| Anna M. Cienciala (hanka@ku.edu) | History 557 Lecture Notes |

Spring 2002 ;revised Feb. 2004; Jan. 20111 |

hist557 by anna m.cienciala is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. Based on a work at web.ku.edu. |

LECTURE NOTES 20. Post-Communist Eastern Europe. ( Revision in process, October 2008).

20A. Central and East Central Europe.

Preface.

The collapse of Communism in Central [Germany], East Central and South Eastern Europe [Balkans] in the second half of 1989 can be compared to the collapse of the three Empires: the Russian Empire in spring 1917, then the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires in November 1918. In both 1918 and 1989, the Baltic Peoples, the Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Croats and Slovenes and some Romanians, were freed from foreign rule, while Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria overthrew their communist leaders. However, after 1989, they had to change not only their political system from one party rule to political pluralism, that is, democracy, but also change their economic system from a command economy to a free market economy, that is, capitalism. The transition to the new politics and economics has proved to be a very difficult process, especially since the economies of most of East European countries were in poor shape. Furthermore, the USSR, with which they did most of their trade, collapsed at the end of December 1991. Also, they had little or no investment capital of their own, and did not receive an equivalent of the Marshall Plan (began 1947), which put Western Europe back on its feet after World War II.

I. Overview of Political, Economic Change and Problems.

Former dissidents provided political leadership before and during the revolutions, but found it difficult to organize viable and coherent political parties within a multi-party system. Most of the idealistic dissidents of the 1980s were replaced by professional politicians, many of whom were formerly members of each country's communist party. Most of them, however, were not ideological communists and they were the only people with political experience .

The change to democracy was much easier than the change to a free market economy because these countries had been bankrupted by an economic system that ignored cost-effectiveness. Most of them also had large foreign debts to the West, plus they lost the Russian markets where they had exported 50-60% of their goods. This market loss was due to the collapse of the Soviet economy which accompanied the dissolution of the USSR in late December 1991.

The German Democratic Republic shared all key characteristics with Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, but it was a special case because it was part of the German nation. A democratized East German state existed for one year after the fall of the Berlin Wall. It joined West Germany in a unified German state in October 1990.

The transition from communism to a free market economy and from a forced dependence on the USSR to independence, is considered by some specialists as largely complete by 1991, but by others as an ongoing process. The author of this text favors the latter view, considering the fact that privatization is still incomplete in 2008, even though the countries in this region have made great economic progress since 1989. Progress, however, was accompanied by many difficulties which were most obvious in the economic sector, especially in Poland, where the first post-Communist government chose a more radical "shock therapy" in economic reform than was the case elsewhere.

Czechoslovakia, or rather the Czech Republic (the country split into the Czech and Slovak republics in Jan. 1993), pursued a more gradual transformation as did Hungary, which was ahead of both countries in having a well-organized banking system. In all three countries, as well as Slovakia, the pain and suffering due to unemployment and inadequate welfare safety nets helped ex-communist -- now mostly Socialist parties-- to increase their membership and voter support, although this petered out after a a couple of years. The only communist party to keep its old name and ideology survives today in the Czech Republic and usually wins 10-12% of the vote.

On the whole, unlike the Russian Federation, the democratic process seems irreversible in East Central and S.E. Europe. All of the above comments also apply to the Baltic States of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, which regained full independence with the collapse of the USSR in December 1991.

Although the Ukrainians overthrew communism in the "Orange Revolution" of fall 2004, Ukraine still has great economic difficulties and needs to develop a national identity shared by all its parts: the western, central and the highly russified eastern industrial region. Ukrainian national consciousness is most highly developed in western Ukraine (former S.E. interwar Poland and before that, East Galicia in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, earlier in pre-partition Poland. W.Ukraine includes Volhynia, formerly in old Poland, then in the Russian Empire, then in interwar Poland.)

Belarus (part of old Poland, then Russian, then partly in interwar Poland) has been ruled since 1994 by the ex-communist former state farm director, President Aleksandr Lukashenka, who does not tolerate any opposition. It is worth noting that the territories of today's Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, most of Estonia, Belarus and Ukraine, were part of the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569, (see map below). The Russian territory between Poland and Lithuania, known as the Kaliningrad region, was created at the end of WW II. The Russian port city of Kaliningrad was formerly the old Prussian city of Koenigsberg (in East Prussia), which suffered almost total destruction in the fighting between Russian and German troops at the end of WWII.

[Map from Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction of Nations. Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, 1569-1999, New Haven and London, 2003; note the present borders.]

The Czech, Hungarian and Polish republics became members of the NATO alliance in March 1999, giving them a much needed sense of security vis-a-vis the potential revival of Russian imperialism.The ceremony took place in the Truman Library, Independence, MO, in the presence of the Foreign Ministers of Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary, with U.S. Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright, presiding. The celebration of NATO's 50th anniversary took place in Washington D.C. in April that year. The government of the Russian Federation strongly opposed the entry of these states into NATO, but had to accept it. The other East European states which later joined NATO were Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania (Russia was especially opposed to their entry into NATO), as well as Slovakia, Bulgaria,Romania, and Slovenia. All these states entered the European Union [EU] and NATO in the years 2004-07

Ethnic-national tensions and conflicts.

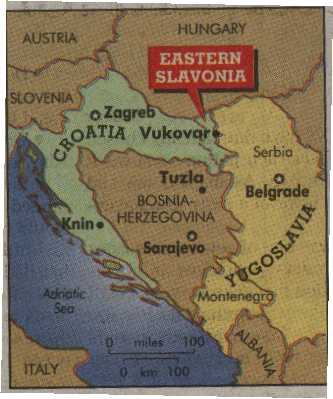

TV allowed people all over the world to see the terrible ethnic-national wars in former Yugoslavia - between Serbs and Croats, also Serbs and Croats versus Muslims in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Serbs versus Albanian Kosovars in Kosovo. [See 20B].

The situation in East Central Europe has been stable, but there are some lesser ethnic-national tensions such as those between the ruling Slovaks and the Hungarian minority in southern Slovakia, also between the ruling Romanians and the Hungarian minority in Transylvania. There has been some tension between Hungary on the one hand and Romania and Slovakia over the Hungarian Status Law. This gave people of Hungarian origin of descent some benefits if they come to Hungary for education or work. Both Romania and Slovakia saw this law as the thin end of the wedge for Hungarian revisionism, although the Hungarian government denied this goal. The issue was finally settled to mutual satisfaction in 2003 when the Hungarian government granted the same benefits to Romanian and Slovak workers in Hungary as to ethnic Hungarians from these countries.

Another contentious issue, this time between the Czech and Slovak Republics on the one hand, and the Germans and Hungarians expelled from former Czechoslovakia at war's end - and now their descendants - on the other, are the Benes Decrees. These decrees, issued by President Edvard Benes in 1945-46, deprived German and Hungarian citizens of prewar Czechoslovakia of their citizenship, property and right of residence because of their hostile activities against the Czechoslovak state in the period 1938-45. Exceptions were made for people who could prove that they had been loyal to Czechoslovakia -- which was generally very difficult. The most numerous expellees were 2,900,000 Sudeten Germans. German, Austrian and Hungarian politicians, as well as the press of these countries, question the legality of the Benes decrees and demand compensation, while Czech and Slovak public opinion opposes it.

The 8,250,000 Germans who fled or were expelled from postwar western Poland - formerly East Prussia and the eastern part of prewar Germany - made up a vociferous, organized group, but lost much of their influence after the German-Polish Treaty of November 14 1990, which gave official recognition to the postwar German-Polish frontier. However, there was some fear among Poles that Germans would buy out Polish land in formerly German areas once Poland joined the European Union. (Some Germans have been buying land through third parties, because it is illegal for foreigners to buy land without special permission.) There is, however, a Polish-German agreement that no land may be purchased by foreigners in Poland for a period of seven years after Poland's entry into the EU (2004 + 7)).

Politicians sometimes make anti-Semitic statements and there are some anti-Semitic political parties and groups in various countries, but they are fringe phenomena. Residual anti-Semitism is just as much if not more present in fringe, extremist movements in Germany and Austria as there is, for eg. in Hungary and Poland. There is also some racism in France, although it is directed mostly at Moslem immigrants from North Africa .

There is widespread hostility to the Roma (Gypsies), who have been particularly targeted in the Czech and Slovak Republics (separated in Jan. 1993), although they are also subject to attacks elsewhere. They are still cultural and social outsiders with whom most people in E. Europe do not feel any affinity. They have been emigrating West, mostly to Britain and Canada, which have restricted their immigration, and lately to Italy, where they are no longer welcome..

Reflections on national states and nationalism in Eastern Europe.

Some western historians and political scientists agree with the British Marxist historian, Eric Hobsbawm, who traces the ethnic-national problems of todayís Eastern Europe back to President Woodrow Wilsonís emphasis on self-determination at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. Hobsbawm expressed this view in his book on world history 1914-91, where he condemned Woodrow Wilsonís insistence on self-determination. He wrote: "The national conflicts tearing the continent apart in the 1990s were the old chickens of Versailles once again coming home to roost."*

*[ Eric Hobsbawn, The Age of Extremes. A History of the World, 1914-1991, (New York, 1994), p. 31. See also an approving, though second hand citation of Hobsbawmís view, that "it was the Wilsonian plan to divide Europe into ethnic-linguistic territorial states, a project as dangerous as it was impracticable, except at the cost of forcible mass expulsion, coercion, and genocide.," Ethnicity and Nationalism in East Central Europe and the Balkans, edited by Thanasis D. Spikas and Christopher Williams, Aldershot, 1999, pp. 80]

However, blaming the so-called Wilsonian principle of self-determination for interwar and recent ethnic-national conflicts in E. Europe is a mistake for the following reasons:

(1) Although Woodrow Wilson did support self-determination as the key principle in drawing up frontiers in E.Europe in 1919, these frontiers were not the result of his influence. In fact, they were drawn almost entirely on site by the former subject peoples of the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires, that is, those who were on the winning side, and this was done even before the Peace Conference opened in Paris on January 12, 1919. The frontiers drawn up in Paris were the Polish-German frontier, the frontiers of the new Austrian state, also the German-Danish, German-French and German-Belgian frontiers.

(2) The post 1919 national states of E.Europe were not the result of a Wilsonian plan or principle. They were, in fact, the implementation in Eastern Europe of the ethnic nationalism that had developed in Western Europe during the 19th century, although they received recognition and support from Woodrow Wilson in 1919.

(3) Except for the mass exchange of Greek and Turkish populations in 1923-25 -- which was the result of the Greek defeat by the Turks in war -- there was no mass expulsion of populations, or genocide, following World War I. Here we should note that:

(a) Genocide took place in Eastern Europe not after World War I, but during and after World War II. This was above all the Jewish Holocaust, but there were also great population losses among other peoples. Therefore, some historians speak of the Polish holocaust, the Russian holocaust, and the Serb-Croat holocaust during WW II.

(b) There was some population displacement after World War I (agreed expulsions of Greeks from Turkey, and Turks from Greece (see 3 above), also of Turks from Bulgaria. The mass expulsions of German populations in 1945-48 were possible because of German defeat in war, but were motivated by German policies in East Central. Europe before WW II (the Nazi use of German minorities in other countries) and during World War II, especially the expulsion of Poles from former W. Poland, annexed by Germany, to the "General Gouvernement," * as well as the use of about many Poles as forced labor in Germany, also of Czechs from the Sudetenland. [After WW II, aside from Poland, Germans were also expelled from Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania and N. Yugoslavia - for map of expulsions, see Lec.Notes 17, Introduction].

*[On German deportations of Poles from former W. Poland, annexed to Germany, to the General Gouvernement (occupied Poland) in 1939-1941, see Philip T. Rutherford, Prelude to the Final Solution: The Nazi Program for Deporting Ethnic Poles, 1939-1941, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2007.The author gives a brief, historical background for German-Polish relations, showing their place in the Nazi policies of expelling Poles and resettling Germans in their place. The view that this process was a prelude to the Jewish Holocaust is correct only in so far as the deportation procedures are concerned. As the author acknowledges, in these deportations the Germans wanted to get rid of ethnic Poles, although Polish citizens of the Jewish race, or faith, were also deported to German-occupied Poland.]

(c). We should note the deportation of some 400,000 Poles to the USSR in 1939-41, while refugees and men conscripted into the Red Army probably raised the number of Polish citizens (Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, Belarusians) in the USSR in 1941-45 to about 1,000,000. The postwar expulsion of the Polish population from territories lost by Poland to the USSR was the result of Soviet westward expansion agreed to by the U.S. and Great Britain at the Big Three conferences of Tehran and Yalta.

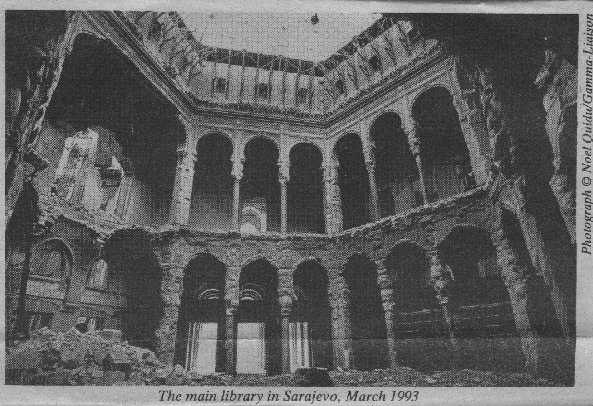

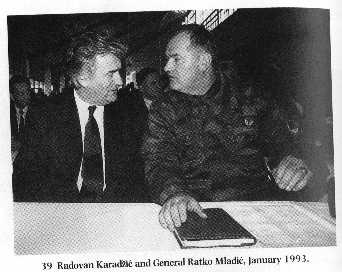

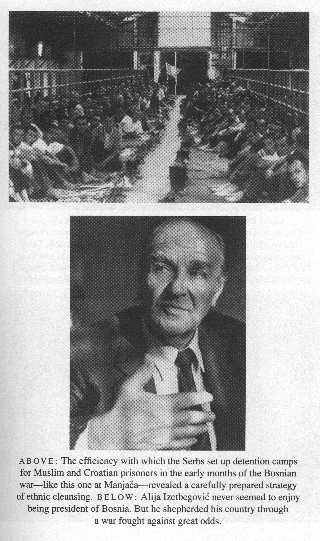

d) The genocide and "ethnic cleansing" that took place in the wars in former Yugoslavia, 1991-95: the Serb- Croat-Muslim war in Bosnia, the Serb-Kosovar war, then Serb ethnic cleansing of Kosovo, 1999, were the result of two factors: (a) claims to the same land by two or three different ethnic nations, and (b) past nationalist conflicts and hatreds manipulated by the leaders.

Thus, none of the atrocities of World War II or those in the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s can be traced back to President Woodrow Wilson and his insistence on self-determination in 1919.

II. The countries of post-communist East Central (or Central) Europe,* BY COUNTRY

*[The State Dept. now uses the term: "Central Europe" for Germany, Austria, Czech and Slovak Republics, Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia, but in these Lecture Notes, the last country is discussed in the section on S.E. Europe; the State Dept. uses the term "East Central Europe" for Belarus and Ukraine.]

A. Poland.

The Communists suffered a humiliating defeat in the elections of 4 June 1989 (see Lec Notes 19A). Once the results were known, the actress Jolanta Szczepkowska announced on TV: "Ladies and Gentlemen - Communism ended in Poland on June 4." Indeed, 160 out of the 161 Solidarity candidates who ran for the 35% contested seats in the Sejm (pron. Seym, Lower House of Parliament), won them in the first round. What is more, people crossed off almost all communist deputies named on their ballots. As a result, only 3 members of the government coalition won seats, and they did so with the support of Solidarity. Solidarity also won 99 out of 100 seats - all open for contest - in the restored Senate.

The Communists acknowledged defeat - apparently on advice from Mikhail S.Gorbachev - while Solidarity leader Lech Walesa and his advisers agreed to a run off election which brought communists into the legislature. In July 3, the KOR and Solidarity dissident Adam Michnik, the editor of the daily Gazeta Wyborcza (Electoral Paper), made his famous proposal: "Your President - our Prime Minister," proposing a Solidarity deal with the Communists. On July 14, Walesa, in accordance with the Roundtable Agreements, appealed for an immediate presidential election from among the party-government coalition. Everyone knew that the only candidate was Gen. Jaruzelski. On July 19, the Sejm gave Jaruzelski 270 votes against 233, with 34 abstentions. (Some Solidarity members deliberately cast invalid votes to lower the threshold of absolute majority). Jaruzelski squeezed by with one vote above the mandatory minimum, and became President of Poland. (He resigned in July 1990). In August, the two satellite parties abandoned their coalition with the PZPR (PUWP - Polish United Workers' Party), and joined the Citizens’ Parliamentary Club (Solidarity), giving the latter a majority. It was not surprising, therefore, that General Czeslaw Kiszczak (pron. Cheslaf Keeshchaak), former Minister of Internal Affairs, and then Mieczyslaw Rakowski (pron. Myecheslaaf Rahkofskee) failed to form a government.

President Jaruzelski turned to Walesa for advice

on who was to be appointed Prime Minister. They agreed on Tadeusz Mazowiecki

(b.1927), a lawyer, journalist, devout Roman Catholic, co-founder of KOR (Komitet Obrony Robotnikow = Committee for the Defence of Workers formed in 1976), and a well known Solidarity

activist. In the Sejm (Parliament), 378 deputies voted for him, with 4 against and 41 abstentions. He

announced the new government on September 12, 1989 with only 9 communists --

including General Kiszczak as Deputy Premier and Minister of the

Interior, and General Siwicki as Minister of Defense - out of

21 ministers. The new government was approved by a majority vote of the

Sejm (402 for, 13 abstentions). According to the Roundtable Agreements, the Communists should have held the ministries of the Interior, Defense, and

Foreign Affairs, but held only the first two - and not for long. Krzysztof

Skubiszewski, (pron. Kshyshtoff Skoobeeshevskee) professor of International Law, Adam Mickiewicz University,

Poznan, and never a party member, became Foreign Minister. Again, it seems that

Gorbachev advised Rakowski (the new head of the PZPR after

Jaruzelski resigned the post when he became president) to accept the new government.

The president's power was considerable, including the right to impose martial

law, so presumably Gorbachev felt that he could well agree to the new Polish

government.

|

Adam Michnik 1999 |

New York Times Magazine, November 7,1999, pp. 70, 72

The Economy.

Meanwhile, before Rakowski's resignation as Premier on July 31,the Sejm voted to create a free market economy as of August 1. This meant that meat ration cards were abolished, and all food prices were free. This led to a price increase of 264.3%, second only to price increases in former Yugoslavia. Thus, the new government faced a very difficult economic situation. It grew worse for a good while due to the "shock therapy" or "the Balcerowicz plan" named after Minister of Finances, Leszek Balcerowicz. He issued a set of ten regulations in January 1990 aiming to restructure the economy - and prices jumped another 585.8% that year, again second only to former Yugoslavia. At the same time, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved the Mazowiecki governmentís reform plan and granted credits of $700 million, plus $1 Ĺ billion from the World Bank.

The new policy was meant to fight inflation, also to reduce foreign debt and the budget deficit. However, it impoverished a large part of the population, leading to rising unemployment and therefore labor strikes. Indeed, the government had to impose price controls on flour and bread in late January 1990.

The old communist party, the PZPR, decided at its 11th Congress to dissolve itself and did so on January 29, 1990. The vast majority of the delegates voted to create a new party: The Social Democracy of the of the Polish Republic (Polish acronym: SDRP). Alexander Kwasniewski, then 36 years old, a former youth activist, Sports Minister, and one of the chief party negotiators at the Roundtable Talks, became Chairman of the Partyís Head Council, while Leszek Miller, 44 years old, was elected Secretary General of the Executive Committee. The new party took over the assets of the old PZPR, but lost 95% of them to later privatization. The minority delegates at the Congress, who supported Tadeusz Fiszbach, lst Secretary in Gdansk, 1980, formed the Polish Social Democratic Union. Unlike the SDRP , they proclaimed a complete break with the old PZPR, but did not manage to survive.

Local government elections took place on May 27, 1990, but only 42.27% of voters chose to vote. (In the U.S. an average 33% of those with the right to vote, participate in elections). Presidential elections were held in December 1990, and Walesa won in the second round, elected President for five years. His most serious rival was an expatriate Pole who won enough votes to produce a second round, while Mazowiecki lost by a large majority. Parliamentary elections were held on October 27, 1991, with a turnout of 43%, and produced a right-wing coalition headed by Jan Olszewski.

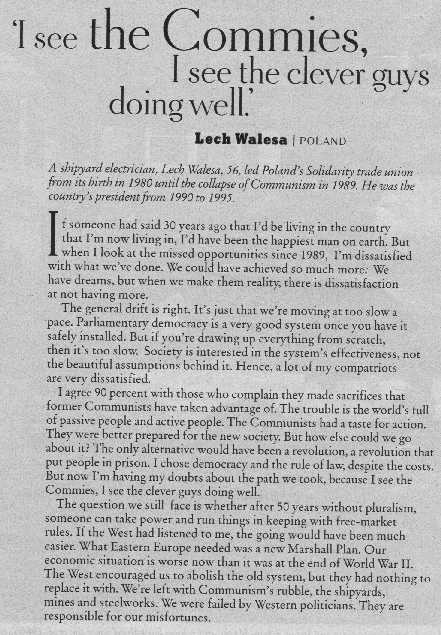

Lech Walesa's Reflections on the East European situation in 1999.

|

|

Note that Walesa was angry at gains made by former communists, a sentiment widely held in Poland. He faults the Western Powers for not establishing a Marshall Plan for E.Europe, and blames the economic catastrophe (of the transition period) on them. One may well sympathize with this view. Of course, the Marshall Plan for W. Europe stemmed from U.S. fear that economic chaos and poverty would lead to Communist electoral victories, especially in France and Italy, which would open the way for Soviet domination of W.Europe. However, the USSR collapsed in late Dec. 1991, so there was no immediate threat of renewed Soviet domination in E.Europe. Therefore, the U.S. and W.Europe did not see the need to give massive economic aid to E. Europe.

Many Polish workers and their leaders saw the source of their impoverishment and unemployment in former communists who became non-communist politicians. In 1996, Marian Krzaklewski, head of the Solidarity Trade Union looked to right-wing parties and used slogans such as keeping abortion illegal and honoring God and Catholicism in the Polish constitution. He claimed that communists and atheists were running the country. * This later developed into the ideology of the right-wing "Prawo i Sprawiedlwosc" (PIS = Law and Justice) Party led by the Kaczynski brothers, who came to power in Oct. 2005 but PiS lost the elections of Oct. 2007. (See discussion of PiS later in this lecture.)

*[see David Ost, The Defeat of Solidarity. Anger and Politics in Postcommunist Europe (Ithaca and London,2005, p.2). Ost argues that Solidarity's political leaders set out to to establish market capitalism, abandoning the workers who had brought them to power. He believes that struggle on the basis of class should continue within a bourgois-capitalist system, otherwise illiberal (undemocratic) politics develop. In post-communist Poland,however, class struggle was so tightly connected in people's minds with communism and the USSR that it was probably impossible to organize political action on a class basis.]

The Polish-German frontier.

Germany was unified in October 1990. German Chancellor Helmuth Kohl at first opposed official recognition of the Polish-German frontier -- and thus the inclusion of Poland in the unification conferenc -- because he feared to lose the votes of those Germans, or rather their descendants, who came from the German territories awarded to Poland in 1945. However, he gave in to pressure from the United States and Britain, so Poland was represented in the third round of the conference, in July 1990, which dealt with Germanyís eastern frontiers.

The Roman Catholic Church.

While communist ministers were replaced by Solidarity supporters, and later by former communists, the Catholic Church exerted great influence on successive governments. This was especially visible on the issue of prohibiting abortion (with some exceptions), which had been voluntary since 1956. After the collapse of Communism, people did not go to church as often as before, but the church remains a powerful influence in the country. Chuch support helps right-wing and moderate candidates in elections, although the Church declares that it does not take sides in politics..

De-Communization.

The Mazowiecki government was criticized later for not undertaking measures of "de-communisation," that is, verification of government officials and politicians to exclude from public life those who had cooperated with the Security Services under Communist rule. However, Mazowiecki followed the general line of toleration and avoidance of vindictiveness that was popular in leading Solidarity circles. Indeed, the opening of the Secret Police files in former East Germany and Czechoslovakia led to many abuses, and the succeeding Olszewski governmentís attempt to use them as a weapon against political opponents proved highly unpopular. (The right-wing government led by Jan Olszewski , resigned Dec. 1991. De-Communisation finally got under way in Poland in 1999. Each person holding or chosen to hold a political post had to declare whether he/she ever worked to the Security Police (SB). There have been a few cases when Ministers, who denied such work, were found to have lied and were forced to resign.)

The elections of September 1993 brought in a preponderantly Left-wing government dominated by the Democratic Left Alliance (SDL) supported by the Peasant Party. This electoral victory reflected the dissatisfaction of the majority of Poles with the painful transition to a free market economy. Indeed, selected economic indicators for Poland in the years 1989-1993 showed a disastrous decline in production, consumption, employment and exports in the year 1990, although a significant recovery began in 1993. It is true that the decline of the GDP in Poland was comparable with Hungary in 1990-92, running at about 17%, and lower than the decline in Czechoslovakia, which was close to 23%, while the Romanian GDP was reduced by about 32% and the Bulgarian by almost 28%. However, this was little comfort for the Poles. *

*[see Kazimierz Poznanski, Polandís Protracted Transition. Institutional Change and Economic Growth, 1970-1994, Cambridge, 1995, p. 193. For an excellent, recent study, see Richard J. Hunter, Jr. Leo V. Ryan C.S.V, "The Ten Most Important Economic and Political Events Since the Onset of the Transition in Post-Communist Poland," The Polish Review, vol. LIII, 2008, no. 2, pp. 183-216. It is summarized and updated in The Sarmatian, September 2008.].

The new left-wing government failed to improve the living conditions of the majority of the population, so it fell in the elections of September 1997, which saw the victory of the "Solidarity Electoral Action" (Polish abbreviation: AWS), a coalition of right and center splinter parties put together by Aleksander Krzaklewski.

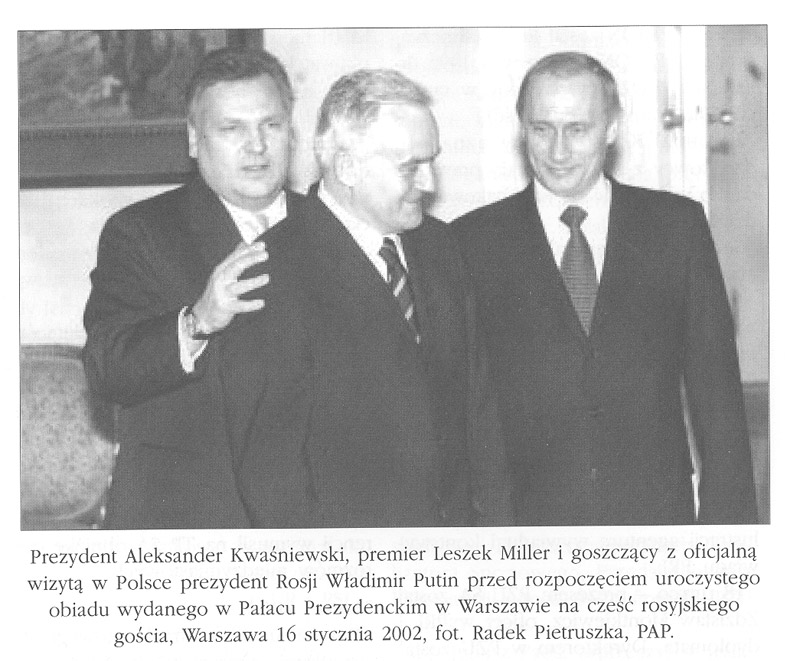

In the meanwhile, in December 1995, Walesa lost the presidential election by a very small margin to the ex-communist, Aleksander Kwasniewski, who used American election campaign tactics. He was re-elected President in 2000 and was the most popular Polish politician of his day, while the right-wing coalition suffered extensive fragmentation and lost the election of all 2001 to a left-wing coalition (SDL). This coalition was very unpopular with the Polish people, who suffered high unemployment with an average 17-18%. (East German unemployment stood at about 22% but welfare payments, funded by W.Germany were very high). Also, the trade unions, including Solidarity [now only a trade union] that represents workers in state- owned, inefficient and debt ridden industries, frequently demonstrated against the government. The most vocal protests were made by the coal miners because the government was shutting down inefficient and unproductive mines. Coal miners used to be the elite of the Polish working class and were very well paid. Many were now unemployed and found it difficult to take up other work. Farmers also demonstrated, demanding guaranteed payments for their produce.

[President Aleksander Kwasniewski, Premier Leszek Miller and Russian President Vladimir Putin, then visiting Poland, 16 January 2002. From Anna Bochwiec, III RZECZPOSPOLITA W ODCINKACH.]

The economic situation greatly improved with Poland's entry into the European Union in 2004. This brought greater foreign investment and allowed many Poles to work in EU countries, thus lowering unemployment at home. In fact, by 2006, about half a million Poles were estimated to work in Gt. Britain and Ireland, while many also worked in Germany. A shortage of skilled labor was noted in Poland while demand for foreign labor dropped in W. Europe. (Some Poles began returning home in 2007, a trend which continued in the financial crisis that began in the U.S. in fall 2008 and soon affected the rest of the world.)

The political situation also changed. In fall 2005, the right-wing Prawo i Sprawiedliwosc (PIS = Law and Justice) party won a significant number of votes in the parliamentary elections and Lech Kaczynski (pron. Lekh Kachynskee) was elected President for 5 years. He promised not to appoint his twin brother Jaroslaw (pron. Yaroslav) as Premier, but soon did just that. The PIS formed a coalition government with two right wing splinter parties: The Samoobrona (Self-Defense) a small peasant party led by Andrzej Lepper and the Liga Polskich Rodzin (League of Polish Families, LPR) led by Roman Giertych, (grandson of prewar and wartime National Democratic leader Jedrzej Giertych, and named after Roman Dmowski, who led the National Democrats until his death in Jan. 1939). The Kaczynski brothers had started out in politics alongside Lech Walesa in Solidarity, then held high office under him as President, but were dismissed and then turned against him, Now they implemented populist, nationalist, right-wing policies. They planned to carry out the "lustration" (verification of non-cooperation with communist security services) of all central and local government officials (est. at 700,000!) and even demanded the lustration of people well known for their opposition to communist rule. The only parliamentarian who refused lustration was Bronislaw Geremek, who had, indeed, been a communist but resigned from the PZPR over the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. He had, in the meanwhile, been an adviser to Solidarity, was imprisoned, and, after the fall of communism, became Foreign Minister and was elected to the European Parliament, where he was highly respected. He had been cleared twice of cooperation with the Security Police when he refused lustration under the aegis of the Kaczynski government. (He died in a car accident in July 2008).

[The twins, Lech and Jaroslaw Kaczynski, during the Parliamentary Session of 29 November 2001, from Anna Bochwiec, III RZEPOSPOLITA W ODCINKACH.)

The PIS-led coalition was already in disarray when it lost the elections in fall 2007. A moderately right wing party, the "Platforma Obywatelska" (pron. Plaatformah Obyvatelskah -- Civic Platform), led by Donald Tusk -- a native of Gdansk with a degree in History and a co-founder of the "Liberal Democratic Congress" in 1991), won a significant number of votes. He had run for President and lost to Lech Kaczynski in 2005. Now, he created a coalition government with the Zjednoczone Stronnictwo Ludowe (ZSL = United Peasant Party), whose leader, Waldemar Pawlak, became deputy Premier (he had been Premier in 1992 and 1993-95). Lech Kaczynski, however, remained as President (elected for 5 years in 2005). He has been following his own foreign policy and criticizing the new government. Also, he has constantly stressed Polish grievances against Germany, Russia, and the European Union, as well as pushing for closer Polish relations with the United States.

In 2005-07, when the Kaczynski-led coalition was in power, they managed to appoint right wingers to leading positions not only at the IPN (Institute of National Memory) but also in Polish public media, especially state TV, all of which continued to publicize their views on domestic politics and foreign policy in 2008. They have also continued their earlier campaign against Walesa, focusing on the charge that he was a Security Police agent from Dec. 1970 to sometime in 1976, and perhaps even later. This charge was first circulated by the Security Police in 1983, in an effort to prevent the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to him, but the award was made and his wife Danuta received it for him. Walesa has always rejected the charge and was cleared of it in the 1990s. He does admit signing a piece of paper for the Security Police to get out of jail and return to his family, after being arrested as one of the strike leaders in the Gdansk shipyard in Dec. 1970. (Indeed, in over almost half a century of communist rule, many people signed agreements to "cooperate" withe Security Police for one reason or another, but this is not the same thing as actually doing so. Most honest people simply tried to avoid harming anyone in their co-called cooperation.) The Kaczynski-controlled media, however, identify Walesa as "agent Bolek," who appears in many Security Police documents of the 1970s. A book titled SB a Walesa (The Security Police and Walesa), produced by two right wing historians, Slawomir Cenckiewicz and Piotr Gontarczyk (published with many SB documents in June 2008 by the Polish Institute of National Memory (IPN. See Lec.Notes 18a). Walesa said he would take the authors to court, but in September stated that he would wait for the law to be changed.On Sept. 29 2008, there were celebrations in Warsaw on the occasion of Walesa's 65th birthday and the 25th anniversary of his receiving the Nobel Peace Prize.

General Jaruzelski was again subjected to a trial in October 2008. He was charged with the "criminal acts" committed under Martial Law. (See Lec.Notes 18A for Martial Law and the trial.)

While the controversy over the book on Walesa and the Secruity Police is ongoing, other events have claimed Polish attention. On August 7, the Georgian army moved into autonomous South Osssetia and bombarded its capital, but were pushed out by a massive Russian counterattack. The Russians routed the Georgian army and also helped autonomous Abkhazia (with ports on the Black Sea) to attack the Georgians. Russian troops advanced into the heart of Georgia and blew up an important railway bridge. An armistice was brokered by French President Nicolas Sarkozy - also president of the European Union -- but the Russians took their time to withdraw. Georgia has received much verbal support from its western neighbors, W. Europe and the USA. The Russian government claims to have acted in defense of Russian citizens in S. Ossetia, but has recognized the independence of S. Ossetia and Abkhazia. It has also emphasized its view that it has a "privileged" role to play in states that were formerly part of the USSR -- which include Belarus, Chechnya, Georgia, Ukraine, and the Baltic States of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, plus Central Asian states..

On August 20 2008,Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski (Raadoslaav Seekorskee) and the U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice signed the "Missile Shield Treaty" and an agreement Polish-U.S. military cooperation in Warsaw . American missiles wiere to be placed in northern Poland. Polish public opinion had opposed the missiles, but swung in their favor after the Russian invasion of Georgia. Sikorski had held out for U.S. financial aid to modernize the Polish armed forces, and managed to obtain it. The treaty involved the positioning of U.S. Patriot Missiles in Poland, while the radar installations are to be placed in the Czech Republic. The Czech government had agreed to these installations earlier, despite much public opposition as well as opposition by Russia. (The Czechs are to be protected, if necessary, by missiles launched from U.S. warships in the Mediterranian.)

The stated aim of these two"Target" treaties is to enable the U.S. to track and shoot down Iranian missiles aimed at the United States. (Their most direct trajectory is alleged to be over Poland.) Russia opposed the treaties and has condemned them, warning Poland that it will now be targeted by Russian missiles. The missiles are to be put on site in Poland by 2012. Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov visited Warsaw on Sept.8, 2008, and, while demanding respect for Russian rights to predominant influence in the territories of the former USSR, expressed readiness to accept the Missile Shield Treaty provided it was accompanied by real guarantees, which would have to negotiated.

As it turned out, the U.S. missiles placed in Poland were unarmed mockups and after the Democratic victory in the U.S. elections of Nov. 2008, President Obama did not go any further. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton presented a "RESET" button to Russian Foreign Minister Ivanov.

The recession which began in 2008 and went into full swing in 2009, focused .U.S.attention on the economy.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

What is the Polish balance sheet for the 19 years following the collapse of communism? Democracy is solidly entrenched, privatization has made good progress, and the country is far more prosperous than in 1989. Only 9.6% of workers were unemployed in June 2008, a great decrease from 2005-2006. Hundreds of thousands of Poles took advantage of Poland joining the European Union [EU] in 2004, to seek work in Western Europe. The largest number found work in England and Ireland. Some have been returning home in summer and fall 2008, especially when the credit crisis, begun in the U.S., has also hit Europe. Poland's no. 1 trading partner is Russia, from which Poland obtains most of its oil and gas. The Poles are now seeking alternate sources of energy.

Four

major reforms, implemented all at once after the communist collapse, caused much chaos, especially in the

Health Service, which is severely underfounded. There was much civil

unrest in the form of peaceful or even violent protests in the 1990s, e.g. by Polish farmers

against the import of foreign foodstuffs . However, some political scientists

argued that this demonstrates the strong hold that democracy has on the country.**

Membership in the EU has helped well prepared farmers since 2004.

**[see: Grzegorz Ekiert and Jan Kubik, Rebellious Civil Society. Popular Protest and Democratic Consolidation in Poland, 1989-1993, University of Michigan Press, 1999. G. Ekiert is professor of Government at Harvard University; J. Kubik is professor of Political Science at Rutgers University].

On the whole, the picture is more positive than negative. Poland is economically better off than Russia and most of the Balkan states, although it lags behind the Czech Republic, Estonia and Latvia.

However, Polish economic progress is far from uniform. On the one hand, the key cities have prospered. Warsaw has been experiencing a massive construction boom for many years and has become a very expensive city. Krakow has become a great tourist attraction, for it has been spruced up and is a pleasure to see in comparison with the drab days of communism. Poznan, Gdynia, Gdansk and Szczecin all demonstrate prosperity while Wroclaw has become a "star" city. Direct foreign Investment has poured in, bringing better returns within 7 years than Paris or Berlin, where returns come after 20 years. The Polish economy grew by about 33% in the period 1995-2000, outstripping Hungary and the Czech republic. * Investment decreased precipitously with the economic recession that appeared in the West that yea, but Polish exports grew by more than 30% since 2004, while exports to Russia alone rose by 75% and the foreign trade share of the GDP in 2008 was about the same.*

*[On the upswing of the Polish economy, see Leo V. Ryan, CSV, and Richard Hunter Jr., "An Interim Report on the Polish Economy," The Sarmatian Review, vol. 28, no. 3, 2008, pp.1418-1421. For more detail, see their article in the Polish Review, v. 53 no. 2, 2008, pp. 183-216.

On the other hand, in medium and small, one-industry towns, the factories or mills have been disintegrating. The inhabitants live off small welfare payments supplemented by their garden plots. One example is Tomaszow Mazowiecki (pron. Tohmaszoof Mazohvetskee), about 100 kilometers (60 miles) south-west of Warsaw. It used to be a textile manufacturing center, but no investor has appeared so far to buy up the outdated mills and modernize them. At the same time, another small town, north of Warsaw, Plock, which used to live off its oil refineries, managed to attract a U.S. Levis producer and acquired a private university, However, the Levis have now moved to Ukraine, where labor is cheaper. This is also true of the manufacture of other consumer goods. (One producer of luxury Polish leather goods, now has its products made in China).

In general, heavy industry suffered greatly, with many workers either laid off or paid an inadequate wage, while tens of thousands of coal miners were laid off with one time benefit payments. The former Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk, the cradle of Solidarity, later renamed the "Pilsudski Shipyard," was sold off in pieces to private investors and many former workers were laid off; some parts are still for sale. Before 2004 (when Poland joined the EU) it was estimated that overall, about 15-20% of the population had become wealthy since 1989 and another 15-20% managed to live well, which left about 55-60% living near or at the poverty level, while the welfare safety net is inadequate. This is not surprising, for welfare is only adequate in wealthy European countries like Britain, France, Germany and the Scandinavian countries. Berlin and Paris are now attempting to cut back welfare payments and health benefits, but are meeting great popular opposition in the process.

The farmers of Poland, still make up 20% of the employed population.The average farm has 5 hectares of land (about 12.35 acres), so it is too small to be efficient. The state farms were dissolved and many were bought up by private investors. However, the collective farms - even the well run ones - were left to rot, along with the people who worked them.

Private farmers borrowed heavily from the government to modernize and found it difficult to pay off their debts. They were hard hit in the early 1990s by western agricultural imports, which were cheaper than their own products due to European Union (UE) subsidies for agricultural goods. Therefore, they protested, sometimes violently, both against foreign food imports and against the lack of adequate, guaranteed, government prices for agricultural produce. Indeed, the main obstacle to Polandís entry into the European Union was EU unwillingness to subsidize Polish farmers, so the vast majority of P. farmers opposed entry into EU for fear they will not be able to compete with its products. The other obstacle is the need to adapt Polish laws to the EU legal system, but this is making progress. As mentioned earlier,well prepared farmers have received funds from the EU since Poland joined the EU in 2004. Some farmers' wives have found well paid jobs in W. Europe, especially as caretakers for older people, but there has also been much exploitation in W. Europe of workers without language and other skills. (Some were found working in conditions resembling WW II labor camps.)

Higher Education and Research

As in all post-communist states, higher education and research have also suffered grievously in Poland from under-funding by the government, as have scholarly publications.

Health.

The Polish health service was reformed in such a way in 1999 that chaos still reigns. It will take both time and money to put the service in order. Meanwhile, private clinics are doing well.

Old Age Pensioners.

Old age pensioners and people earning low wages are often forced to leave their formerly subsidized apartments when private owners decide to sell the house or rent it out for higher prices.

The Ethnic makup of contemporary Poland.

Poland is more ethnically homogeneous than it has ever been, with minorities making up about 5-7% of the total population of some 40 million today*

*[see: Tadeusz Piotrowski, POLANDíS HOLOCAUST. Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic,1918-1947, Jefferson, N.C. and London, 1998, p. 260; Gabriele Simoncini, "National Minorities of Poland at the End of the Twentieth Century," The Polish Review, vol. XLIII (43), 1998, no. 2, pp.173-194].

However, minorities are much more visible than in the communist era. The German minority, located mostly in Silesia, has its deputies in parliament, also its own press and radio stations, while the German language is taught in schools by teachers coming from Germany. There have been clashes with ethnic Poles when German and Polish Silesians built or tried to build monuments to their Wehrmacht (German Army) dead. Silesians were subject to conscription into the Wehrmacht, but many of Polish descent deserted to the allied armies, esp. the Polish 2nd Corps in Italy. Those sent to the Russian front were either killed or used for forced labor after capture.)

There was a latent fear in Poland that Germans would come in and buy up land in western Poland once the latter entered the European Union. For this reason, the Polish parliament passed a law prohibiting sale of land to foreigners for 20 years without the permission of the government. (This is contrary to EU legislation and a compromise 7 years period after Poland jonied the EU was agreed that year, i.e. 2004).

There is also a movement with roots in the pre- World War I and interwar periods demanding recognition of a "Silesian minority," which is neither Polish nor German. However, as of now, it is weaker than the recognized German minority which benefits from German financial support.*

*[see: Karl Cordell, Tomasz Kamusella and Karl Martin Born, "The Articulation of Identity in Silesia since 1989," in: Karl Cordell, ed., The Politics of Ethnicity in Central Europe, Houndmills, Basingstoke, England, and New York, 2000, ch. 7, pp. 161-187; K. Cordell is a political scientist specializing in German and Polish politics, also German-Polish relations, who was then teaching at the University of Plymouth, Great Britain; K.M. Born, a German scholar, was then a Senior Research Fellow there; Tomasz Kamusella is a specialist on the politics of identity in Silesia, who has taught at the University of Opole, Poland and worked in the Provincial Administration there and has recently been teaching at Trinity College, Dublin. NOTE: Five of the eight chapters in this collective work deal with Silesia. The book has a very useful list of place names with Polish and German versions, a Chronology of Silesian history, maps, end notes to chapters and an index].

There are only a few thousand Jews still living in Poland, mostly old people. There is some residual anti-Semitism, but occasional acts such as painting swastikas on walls, or the destruction of headstones in cemeteries, are generally confined to "skinheads" or extreme right-wing youth groups, which is also the case in other European countries. There are legal conflicts over the return of private property to the descendants of Polish Jews. The Polish government takes the stand that religious property must be returned to religious bodies, but the return of private property cannot differentiate between Jews and non-Jews, for many Christian Poles also lost their property either to the Germans in World War II, or to confiscation- nationalization by communist regimes after the war. (It should be noted that no compensation has, as yet, been paid to Polish landowners who lost their property in former eastern Poland, although it can be claimed that those who settled in former German territories were compensated with land there. Most of those people, however, had very small farms before WWII.)

There are positive aspects to the Polish-Jewish

relationship. There is an annual festival of Jewish culture in Krakow and since 1989 "Marches of the Living" take place at Auschwitz (P. Oswiecim)

to commemorate the victims of the Jewish Holocaust. On May

2, 2000, the President of Israel, Ezer Weizman and the President of Poland,

Aleksander Kwasniewski, led the annual march.

Some 5-6,000 young Jews and 800-1,000 young Poles took part in the march.

Kwasniewski called on the young Jews to put historical prejudice behind

them and see the Poles as their friends. Both Walesa and Kwasniewski have expressed deep regret for crimes committed by Poles against Jews in World War II. Finally, Polish and Israeli historians

have been working on new school text books which will discuss the Jewish Holocaust

in German-occupied Poland in a manner avoiding mutual hostility or recrimination. Polish school children now learn about the Jewish Holocaust at school.

There is some friction with the Ukrainian minority. While most of Polandís Ukrainians live on the western Baltic coast -- where their grandparents or parents were forcibly resettled from south-eastern Poland in 1947 in "Operation Vistula" -- the main point of friction is near the Polish-Ukrainian frontier in the town of Przemysl (pron. Pshemysel), which has a small but vocal Ukrainian minority. At the same time, while official Polish-Ukrainian relations are good, conflicts persist, e.g. over the renovation of the Polish military cemetery in Líviv (P. Lwow), where Polish soldiers killed in the Polish-Ukrainian war of 1918-19 are buried. (The L'viv City Council obviously dislikes honoring the Poles for defeating the Ukrainians at that time).

There is also frictionin south-eastern Poland over the building by Ukrainians of monuments to heroes of the Ukrainian Insurrectionary Army (Ukr. acronym: UPA), some of whose units (esp. the Bandera faction of UPA) murdered about 60,000 Poles in former Volhynia in 1943-44, in order to cleanse the area of Poles. Polish and Ukrainian heads of state have exchanged apologies for the past, but Ukrainian and Polish resentment lingers on. In July 2003, the Polish and Ukrainian Presidents -- Aleksander Kwaniewski and Leonid Kuchma -- made conciliatory declarations on the Ukrainian Insurectionary Army (UPA) massacres of Poles in Volhynia in 1943 and Polish retaliation against the UPA. However, west Ukrainian opinion generally blames the Poles for murdering Ukrainians and is reluctant to acknowledge the crimes of the Bandera faction in the Volhynian UPA. Both sides also committed atrocities in East Galicia.The Poles, for their part, don't like to admit that the Home Army, in retaliation, carried out some atrocities against Ukrainians, and that Polish Communist Security Forces carrying out "Operation Vistula" in 1947 were also guility of atrocities.*

*[On the Ukrainian ethnic cleansing of Poles in Volhynia in World War II, see Lec. Note 19, Introduction].

Polish Relations with Lithuania and Belarus; Lithuanian and Belarusian minorities in Poland.

Official Polish-Lithuanian relations are good, but in the early 1990s the Lithuanian government discriminated against its Polish minority, which made up about 9% of the total population and is stil concentrated in the Vilnius [Polish: Wilno] region. This was mostly due to the fact that part of this minority supported continued union with the USSR when the majority of the Lithuanian population wanted independence in 1988-89. The Poles feared Lithuanian discrimination and this, in fact, came into being with Lithuanian independence in 1989-1990. The situation has improved since that time, but in September 2008 the Lithuanian Post Office issued an envelope with pictures of Hitler, Pilsudski and Stalin, labelling them as the murderers of the Lithuanian people. Jozef Pilsudski had Polish troops seize the then predominantly Polish city of Wilno (Lith. Vilnius, Rus. Vilna), in October 1920, which was passionately resented by the Lithuanians who claimed it as their capital on historical grounds. (It was the capital of medieval Lithuania.) Pilsudski was not, however, a dictator on the model of Hitler or Stalin, and he did not murder Lithuanians.

Polish-Belarusian Relations.

Polish local administration policyin the Bialystok region has at times been repressive toward the Belarusian minority . The Polish government, however, supports the opponents of Belarussian President Aleksander Lukashenka, president since 1994. The Belarusian government, in turn, makes it difficult for the Polish minority to have the Polish language taught in schools, and to have Polish priests and churches.

Polish-Russian relations

These relations have been officially correct, although at times far from cordial. It took the Polish government -- under President Lech Walesa-- until 1993 to secure the withdrawal of the last Russian troops. They left behind devastated buildings as well as land ecologically damaged by gasoline dumps and military exercise areas (same in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and the former German Democratic Republic, now part of united Germany). Poland borders on Russia in the Kaliningrad region (in former East Prussia). Moscow has tried, but failed to obtain a "corridor" through Polish territory to this militarized port city. (Transport goes by sea, also by rail through Lithuania).

President Boris N. Yeltsin once told President Walesa

when visiting Warsaw in 1993, that Russia would have no objection to Poland joining

NATO, but he must have been in his cups because the Russian government continued

to object, although it had to accept the fact in 1999. Polish trade

suffered greatly from the breakdown of the Russian economy when the USSR disintegrated in late 1999. It used

to take some 50% of Polish exports, but in 2008 75% of Polish trade was again with Russia. (This, however, improved a great deal in 2009-10 because of the change of government in Poland and the Smolensk air catastrophe of April 2010, for which see below).

Above all, there are serious Polish-Russian disagreements on interpreting the past.

1. Some Russian historians continue to defend the Ribbentrop-Molotov Non-Aggression Pact of August 23 1939, with the German-Soviet Partition of Poland (Secret Protocol). They claim the pact was mandated by Soviet security needs, even though it brought the German armies that much closer to Moscow. In October 2008, a retired Russian general came forward with 700 pages of documents allegedly showing that Soviet generals had proposed a massive Red Army strike at Germany in mid-August 1939, if Poland agreed to their transit to the German frontiers. (The Sunday Telegraph, London, report of Oct.20, 2008). It is most unlikely, however, that Stalin would have risked a war with Nazi Germany in fall 1939, especially if he knew that the French and British General Staffs had secretly agreed on a defensive posture in case Germany attacked Poland.

Indeed, the Soviet-German partition of Poland put the Germans nearer to Russian territory and resulted in the Wehrmacht reaching the outskirts of Moscow by late October 1941. They might have taken the capital if there had not been an early winter, or if Hitler had left enough armored divisions near Moscow to defeat Georgy Zhukov's counter-attack of 6 December that year.* However, Hitler assumed Moscow would fall and sent these divisions to the Caucasus to seize Soviet oil production. German forces were also besieging Leningrad for almost three years.The Red Army pushed the Germans away from Moscow; defeated them in the Battle of Stalingrad, Feb. 1943, and decisively at the Battle of Kursk in July 1943. From that time on, the Germans were in retreat, but fought tenaciously to the very end.

*[See Andrew Nagorski's book: The Greatest Battle: Stalin, Hitler and the Desperate Struggle for Moscow that Changed the Course of World War II, New York, Simon & Schuster, 2007.]

2. The Katyn Issue in Polish-Russian Relations.

While acknowledging in 1990-92 that the NKVD executed 21,857 * Polish prisoners of war in spring 1940 by order of Stalin and his Politbureau, some Russian historians and Russian media continued to accuse the Poles of perpetrating a "Katyn" of their own by murdering 60,000 out of 100,000 Red Army soldiers taken prisoner in the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-20, (mostly in summer-fall 1920), who did not return home. Polish historians, for their part, pointed out that about 65,000 Russians did go hom, also that most of those who died fell victim to malnutrition and disease, especially the typhus epidemic, which also killed many Poles. Also, some prisoners joined "White Russian" units and fought against the Bolsheviks, while others escaped, melting into the Polish countryside. In early 2001, Wladyslaw Bartoszewski , then Polish Foreign Minister, presented Polish documents on the above question to the Russian government when he visited Moscow, but some Russian historians continue to write about a "Polish Katyn" in 1919-1920. Some progress, however, has been made, at least by professional historians. Polish and Russian historians collaborated on a book on the Red Army men, prisoners of war, in Polish captivity: Krasnoarmyetsy w Polskim Plenu, 1919-1922. Sbornik Dokumentov i Materialov, (Moscow, 2005). The Polish scholars arrived at the figure of 16,000 dead, while the Russians arrived at 18,000. Both figures were nowhere near the 60-65,000 previously claimed by some Russian authors. We should also note that about 50% of Poles taken prisoners by the Bolsheviks did not return home. They probably died of the same causes as the Red Army men -- malnutrition and disease.

*[Of the figure of 21,857 Polish victims, 14,552 were from the 3 special NKVD prisoner- of- war camps at (1) Kozelsk (murdered at Katyn near Smolensk);(2) Ostashkov (murdered in the NKVD jail, Kalinin, now Tver, and buried in nearby Myednoye); and (3) Starobyelsk (murdered in the NKVD jail, Kharkiv, and buried in the park nearby), while 7,305 others were murdered in NKVD prisons in western Belorussia and western Ukraine. For the total figure and its breakdown, see: Note by Chief of KGB USSR, A. Shelepin to Nikita S. Khrushchev, March 9, 1959, in which Shelepin gave the total figure and suggested the destruction of the prisoners’ personal files (which seems to have been done) but keeping the records of the judgments by the Troika (Threesome) appointed to this task (apparently also destroyed), in: KATYN. A Crime Without Punishment, edited by Anna M. Cienciala, USA; Natalia S. Lebedeva, the Russian Federal Republic; and Wojciech Materski, Poland, Yale University Press, 2007 (appeared in late January 2008; reprinted 2009).

Four Polish volumes of Russian Katyn documents were published in Warsaw in 1995-2007. Two Russian volumes appeared in Moscow in 1997, 2001. All these volumes were edited jointly by Lebedeva and Materski. The Eng. lang. volume contains 122 documents selected from their work. Anna M. Cienciala wrote new introductions and gave additional information in the end notes. ]

Polish and Russian military cemeteries were opened in Katyn, Kharkov and Myednoye in summer 2000, with separate but neighboring burial sites for Poles as well as Soviet citizens whose deaths were due to Stalin's policies. The Soviet, later Russian, investigation of the Katyn Crime, begun in 1991, ended unofficially in September 2004 and officially in March 2005 with the conclusion that there had been no genocide or a crime against humanity, but that the Soviet authorities involved had acted beyond their authorization,a crime according to the Soviet Criminal Code of the time, and as such, subject to the statute of limitations. Moreover, the persons accused, notably Stalin and Beria, were dead, so they were not subject to judgement. (This is according to Russian law.) The victims' families and Polish public opinion were outraged by this conclusion. A Polish investigation began in November 2004.

There has been no official apology from Moscow, although the Soviet government of President Mikhail S. Gorbachev, expressed "its deep regret" for "a heinous Stalin crime" in April 1990, when it finally acknowledged the NKVD had murdered the Poles in 1940 (Soviet press communique, April 13, 1990. The blame was placed on Beria, then head of the NKVD, and his deputy, Merkulov, with no mention of Stalin.) Also, President Boris Yeltsin was heard asking for forgiveness on visiting the Katyn monument in Warsaw in 1993. Poles do not consider this, however, to be an official apology.

At a press conference during his state visit to Warsaw in January 2002, President Vladimir Putin said that Stalinist crimes cannot be put on the same level as Nazi crimes (i.e. genocide.). His statement should be seen in the context of the Russian admiration of the heroism of the Red Army and the Russian people in the "Great Fatherland War," which was led by Stalin and ended in a smashing victory over Nazi Germany, so anything that casts a shadow on the above is resented.However, the Katyn massacres were not carried out by the Red Army and the Russian people are not blamed for them. It was Stalin and his Politburo who ordered the massacres or forced labor not only of Poles but also of millions of Russians, Ukrainians, and other Soviet citizens.

It is true that Stalin did not use gas chambers to kill his enemies. Many of them were shot, but most of those arrested for alleged anti-state crimes died of what was known in the camps as the "sukhyi rasstrel" (dry shooting), that is, not from a bullet but from disease and exhaustion.** Finally, while the Russians always remember that the Red Army liberated the peoples of Eastern Europe from the Germans, most Russians do not acknowledge that communism and Soviet domination were forcibly imposed on these countries, leading to more loss of life, the imprisonment and mistreatment of thouseands of people,economic hardship, lies about Polish history, and other suffering. Besides the above, Stalinist crimes against both Soviet and other peoples, though much discussed and condemned in the late 1980s - early 1990s under Gorbachev, do not generate much interest among most Russians today. On the contrary, the prevalent view, strongly propagated by the Russian government under President Putin, and now under President Medvedev, is that Stalin was a great leader who modernized the USSR, with some inevitable mistakes on the way. Most important of all, he led the Red Army to victory against Nazi Germany.

President Putin, during a state visit to Warsaw in early 2008, finally called Katyn " a Stalinist crime," but the draft of a Russian history textbook for schools, while acknowledging it as such -- portrays it as justified revenge for the (alleged) Polish murder of Soviet prisoners of war in 1919-1920 and after (August 2008). As mentioned earlier, a projected Russian history textbook for schools presents Katyn as justified revenge for the alleged Polish murder of Soviet POWs in 1920.***

**[For the "sukhyi rasstrel," see Jacques Rossi, Gulag handbook : an encyclopedia dictionary of Soviet penitentiary institutions and terms related to the forced labor camps, translated from the Russian by William A. Burhans, New York, 1989.)

[*** Russian Press, Aug. 25, 2008].

Polish-Russsian Realtions began to change for the better with the election of a center-right coalition government headed by Donald Tusk in October 2007. Tusk took a more friendly line toward Russia, although Lech Kaczynski, elected president for five years in 2005, pursued an overtly anti-Russian line on his own, particularly in supporting Georgia against Russia in 2008. Nevertheless, on Sept. 1, 2009, Putin (Russian Premier since mid-2008) attended the 70th anniversary of the German attack on Poland on Sept. 1, 2009, in Gdansk, and condemned the Secret Protocol to the Nazi-Soviet Pact of Aug. 23, 1939.

Putin and Tusk met again at Katyn on April 9, 2010, where they made speeches to commemorate the massacre of Polish prisoners of war on Stalin's order in spring 1940. This was the first time a Russian Premier had come to Katyn. On the following day, April 10, the plane carrying President Lech Kaczynski, with his wife as well as 96 officials and prominent Poles, crashed in fog at Smolensk airport.This was a terrible tragedy for the Poles, and doubly so for taking place ner Katyn. The Russian leaders, Premier Putin and President Dmitri Medvedev, expressed their condolences, while the Russian people showed their sympathy by bringing flower to the Polish embassay in Moscow and a day of mourning was proclaimed in Russia.

Most Poles appreciated Russian sympathy but President Lech Kaczynski's brother, the leader of the Law and Justice Party (PiS), Jaroslaw Kaczynski, immediately expressed the view that Lech and his delegation had been murdered. He and his party charged the Tusk government with responsibility while others spoke of a Russian plot. Despite these charges, the Russian government followed a policy of conciliating Poland. President Medevev expressly condemned Stalin for the Katyn massacre in late April and again during his state visit to Warsaw in early December 2010.

In the meanwhile, Jaroslaw Kaczynski obtained church permission to have his brother and sister-in-law buried at Wawel Castle, Krakow, where famous Poles are buried. This met with widespread disapproval since the late president's achievements did not qualify him for this resteing place. Furthermoe, Jaroslaw's supporters placed a cross in front of the Presidential Palace, Warsaw, and vowed to stay there until a monument was built in this place to Lech Kaczynski. After several weeks, the cross was moved to a church. In the June 2010 Presidential Elections, J. Kaczynski lost to Bronislaw Komorowski, and the PiS party also lost the local government elections in November.

As Polish and Russian commissions invetigated the causes of the Smolenski catastrophe, Jaroslaw. Kaczynski sent two emissaries, former For. Minister Fotyga and former head of State Security, Macierewicz. to Washington to lobby congressmen for support of an international commission to investigate the catastrophe, but they did not succeed. In December, Premier Tusk publicly expressed his disappointment with the report of the Russian commission of investigation,which was resented by Moscow.

In fall and early winter 2010, however, Polish-Russian state relations continued to improve. In late November 2010, the Russian Duma (Legislature) overhelmingly supported a resolution condemning the Katyn massacre and Stalin for ordering it. The conclusion of this resolution stated that: the victims "had been rehabilitated by history." This was welcomed by Polish public opinion but left open legal questions such as: classifying the crime (a war crime,a crime against humanity, genocide, or a combination of these), and rehabilitating the individual victims, that is, legally affirming their innocence. The Russian Memorial Society and the Polish Katyn Families (which have stated they are not demanding any financial compensation), have been fighting for the resolution of these questions, also accessibility to all the documents collected by the official Soviet, then Russian Katyn Investigation, which had been closed by the Russian Military Prosecutor's Office in March 2005. President Medvedev saw to it that some 90 vols of the Russian Katyn investigation were turned over to Poland. (The total number known to exist is over 800.).The head of Memorial's Polish Section, Aleksandr Gurianov, had been supporting the rehabilitation of individual cases brought by victim families to Russian law courts, but after meeting a blank wall the Katyn case was sent to the International Justice Tribunal in the Hague.

Interpreting the recent past: Was communist Poland a semi-sovereign state?

There has been much discussion in Poland on how to characterize the communist "Polish People's Republic," later "Peopleís Poland," 1944-1989: was it a semi-independent state, or a satellite? Should it be called the "Third Republic." [The Polish state which was partitioned in 1772-95 was the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Commonwealth is a translation of the Latin Res Publica = Public Matter) which is called "The First Republic." This is because Kings had to obtain the support of the nobles in parliament for their policies. The "Second Republic" was Independent Poland, Nov. 1918- Sept. 1939. The term: "Third Republic" is now used mainly by right-wing Polish political parties to denote post-communist Poland in 1989-2005. (The elections of 2005 brought to power a coalition of right wing parties led by "Law and Justice" headed by the Kaczynski brothers, but they lost the elections of October 2007 to the moderately conservative coalition of "Platforma Obywatelska" (Civic Platform) and the "Zjednoczone Stronnictwo Ludowe" (United Peasant Party), led by Premier Donald Tusk. The short-lived PiS coalition period is sometimes called the "Fourth Republic."

Right wing historians deny Peopleís Poland any independence and condemn it wholesale, while left-wing sympathizers emphasize its national character and the positive aspects of its legacy, such as mass education and the resulting social mobility of workers and peasants. Finally, moderate historians see an increase of Polish Communist governments' elbow room in domestic affairs after October 1956.* Right wing historians also portray the Polish governments of 1989-2005 as dominated by communists. (In fact, they included post-communists, the prime example being Alexander Kwasniewski, President in 1995-2005.)

*[ An excellent, brief survey of the dispute over the character of "People's Poland" can be found in Andrzej Paczkowski, "Communist Poland 1944-1989: Some Controversies and a Single Conclusion," Polish Review, vol. 44, no. 2, 1999, pp. 217-225].

B. Czechoslovakia; the Czech and Slovak Republics.

The first democratic elections were held in Czechoslovakia in June 1990. They resulted in a resounding vote against communism because the people voted for the "Civic Forum" in the Czech lands and for the "Public against Violence" in Slovakia. However, these two coalitions soon differed over economic and constitutional issues.

The conflict over economics was between proponents of a speedy transition to the free market and those - former communists and socialists - who wanted a gradual transition with built-in safeguards to maintain living standards. When Finance Minister Vaclav Klaus was elected head of the Civic Forum in October 1990, reforms for a fast transition began. The currency was devalued by 54.5% and privatization took off. Prices doubled in Jan. 1991. The budget was balanced in 1992. The effects of these reforms were harsh. Production and real wages fell and so did foreign trade, which was the result of collapse of the Comecon (Communist Economic Cooperation bloc), especially the Soviet markets.

The Czech conflict with Slovakia was another result of economic reforms - for unemployment in Slovakia was over twice that in the Czech lands (10% versus 4%). Slovak heavy industry, especially armaments, depended heavily on the Soviet market, which deteriorated after 1989. No wonder the Slovaks turned against the shock therapy implemented by V. Klaus .Economic suffering strengthened old resentments against the Czechs. These were manipulated by the former communist leader - and ex-boxer - Vladimir Meciar who emerged as a Slovak nationalist.

In the Czech lands, the elections of January 1992 swept away many idealists who had led the November-December "Velvet Revolution" of 1989. The elections brought in professional politicians. Klaus' ODS (Civic Democracy Party) won the largest number of votes in the Czech lands. Klaus was at logger heads with President Vaclav Havel, whose term of office ended in Dec. 2002. He was succeeded as President by none other than Klaus, but the Czech parliament elected him by the margin of only one vote.

Jirina Siklova, smuggled books to Czechoslovakia from the West, - She became head

of the Gender Studies Dept., Charles IV University, Prague.

[New York Times Magazine, November 7, 1999, p. 80.]

In January 1992, the Slovak National Council approved a declaration of sovereignty, though not independence by 113 votes to 24. Meciar wanted complete economic autonomy, which meant state subsidies for industry and slowing down privatization - neither of which Klaus would accept. He saw the Slovaks as impeding his reforms and pressed for separation. At the same time, Slovak opinion was turning more against the Czechs. Nevertheless, it is important to note that there was no absolute majority among Czechs and Slovaks in favor of separation; even in September 1991, when opinion polls showed only 46% of Czechs and 41% Slovaks were for it.

In fact, the agreement to separate the two nations was made by the politicians, Klaus and Meciar, both of whom opposed a plebiscite (referendum) on the matter. The Federal Assembly voted for separation on October 1, 1992, but the majority failed to reach 2/3 as mandated by the constitution. On November 25, 55 opposing deputies abstained, so a majority was achieved. Despite appeals by President Havel and the work of many Slovaks supporters of the union, the two parts of Czechoslovakia became separate states on Jan. 1, 1993.

In the Czech Republic, economic reforms continued and Klaus was the most popular leader in September1993 after President Havel. But a left-wing party, the CSSD (Czech Social Democratic Party), led by Milos Zeman opposed Klaus and his reform program in favor of slower transition and a larger safety net. Indeed, by 1996, the CSSD was close behind Klausís ODS (Civic Democratic Party), with 26.4% of the vote. Klaus and his party suffered setbacks in late 1996 and in 1997 due to financial and banking scandals. Finally, he was forced to resign due to another scandal (donations to his party) in 1998, but was elected President in December 2002 and re-elected in 2006.

The Czech economy is in very good shape; it has benefitted from large foreign investment, especially from Germany. It is the first country among the former Comecon (Communist Common Market) to be recognized as a "developed" country (2006). It also ranks first among former communist states in the Human Development Index. *

*[see: Czech Republic, Wikipedia, 2008).

In ethnic relations, we should note the rise of racism and xenophobia in the Czech and Slovak republics, as instanced especially by discrimination against and attacks on the Roma (gypsies). This led to mass Roma emigration, both legal and illegal, especially to Britain and Canada, so that both countries took measures to restrict it.

In Slovakia, initial economic hardship reduced

Meciarís popularity, He lost power in spring 1994 but regained it in

the September election that year. He soon established an authoritarian regime,

which, along with acommunist- style economic policy, isolated the country from

the West. He developed close ties with Russia, on which Slovakia depends

for all of its natural gas and 80% of its oil, while exporting aircraft engines

in return. The economic situation improved and Meciar manipulated Slovak nationalism

to his advantage, so he was able to stay in power until October 1998.

The new government of Mikulas Dzurinda that came to power at that time launched an ambitious program of economic reform aiming at a rapid transition to the free market. On April 2000, Meciar was arrested by a Swat-like team which dynamited his back door to get into the house. He was charged with corruption (paying illegal bonuses worth $350,000 to his cabinet ministers), but released on bail pending trial. Dzurinda retained power after the parliamentary elections of Oct. 2002. Slovak economic development has been impressive and the country became a member of both the EU and NATO. It is, however, 100% dependent on Russian oil and gas.

Slovak-Hungarian relations have had their ups and downs. Slovaks have pursued a policy of assimilation toward the large Hungarian minority in the southern part of the country, which has led to tensions with Hungary. *

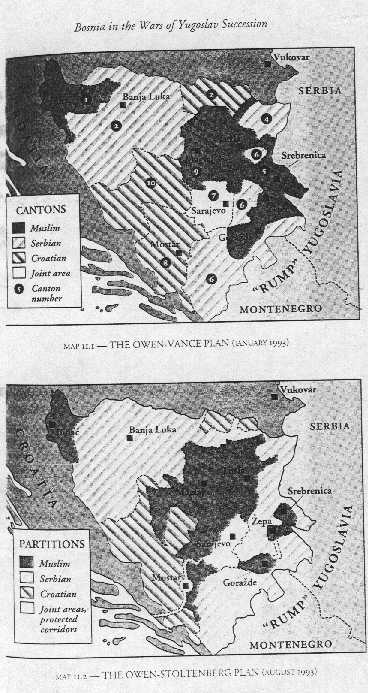

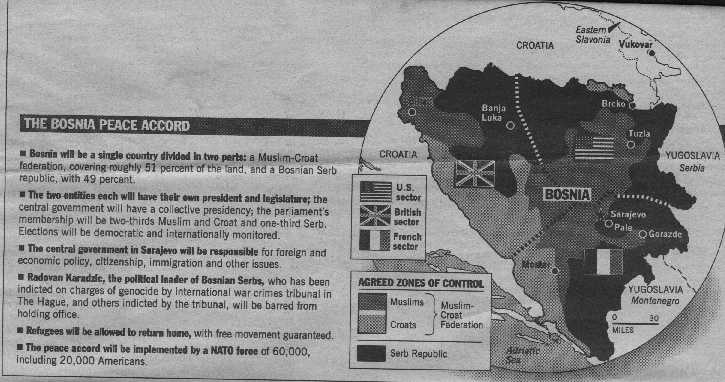

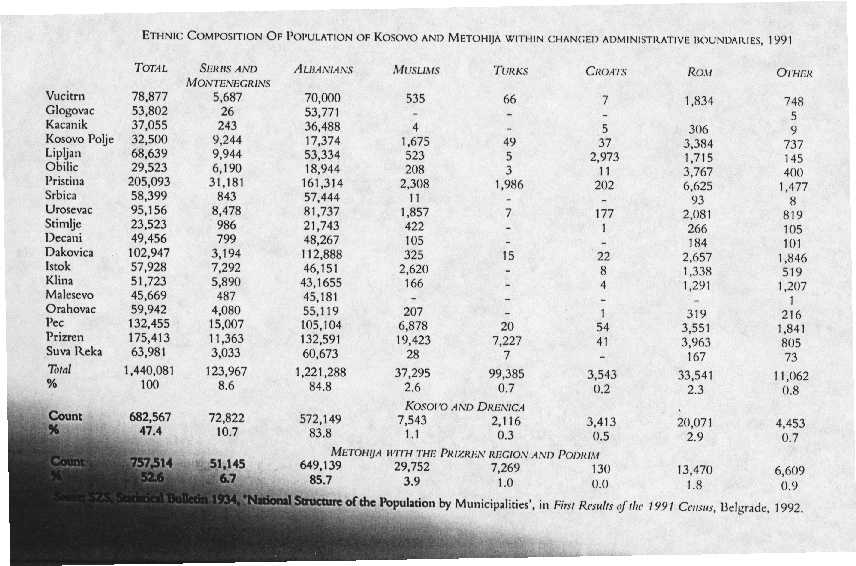

*[See: Tunde Paskas, "The Influence of Language Policies on Slovak-Hungarian Relations in Slovakia," Analysis of Current Events, Nov-Dec.1998, vol. 10, nos.11-12, published by the Association for the Study of Nationalities in Eastern Europe and ex-USSR, pp. 5-6].